1. Introduction

Population ageing is a critical global challenge reshaping economies and societies. As life expectancy rises and birth rates fall, the proportion of elderly individuals is increasing rapidly—a trend known as the "epidemiologic transition." This shift has moved the world’s health focus from infectious diseases to chronic conditions like heart disease and dementia. By 2017, 91 countries had over 7% of their population aged 65+, compared to just 37 in 1960. Nations like Japan (27% elderly) and Italy (23%) now lead this demographic shift, while regions like Sub-Saharan Africa remain younger. These changes demand urgent policy action to address healthcare costs, labor shortages, and economic sustainability.

Economically, ageing populations strain systems. A shrinking workforce risks slower GDP growth and higher public debt, as governments fund pensions and healthcare [1]. Wealthier countries, such as Sweden, face pressure to reform pension systems, while developing nations struggle with weak social safety nets. However, ageing also creates opportunities: demand surges in healthcare, elder care, and technology tailored for older adults. Meanwhile, younger regions like Sub-Saharan Africa could attract global industries due to their growing labor force [2].

This project compares how developed and developing economies adapt. For example, New Zealand uses immigration to offset labor shortages, while Taiwan invests in retaining older workers and expanding community eldercare [3, 4]. These strategies highlight the need for localized solutions. Developed nations leverage resources for healthcare and automation, whereas developing countries focus on education and foreign investment to build sustainable systems.

Within this dissertation, it also study solutions for addressing the issues led by the aging population, and this would mean technology and training, policy reforms, and healthcare investment. Technology and training can help by automating industries and retraining older workers to bridge skill gaps. Policy reforms are being implemented through raising the retirement age, encouraging gender equality in the workplace and reforming pension systems. Meanwhile, long-term costs are being reduced through prioritizing preventive care to promote investment in health care.

The case studies of Italy and Sweden illustrate the consequences of inaction. Italy’s low birth rate and labor participation (48.7% in 2019) contrast with Sweden’s proactive pension reforms, which balance employer-employee contributions to sustain retirees [3]. These examples underline the importance of adaptability.

In conclusion, population ageing is not just a crisis but also a catalyst for innovation. By blending policy creativity, technology, and equitable practices, societies can transform demographic challenges into opportunities for growth. This project explores these dynamics, emphasizing the need for urgent, strategic action to ensure economic resilience in an ageing world.

2. Research review

2.1. The issue of the ageing population

Population ageing is a growing global issue that affects public health. In the past, health problems like infectious diseases and parasites mainly affected infants and children. Now, as more people grow older, non-communicable diseases like heart disease, arthritis, and dementia are becoming the biggest health concerns worldwide. This change in health problems is called an "epidemiologic transition." To address the challenges of an ageing population, it’s necessary to study both its current effects and how it’s changing over time.

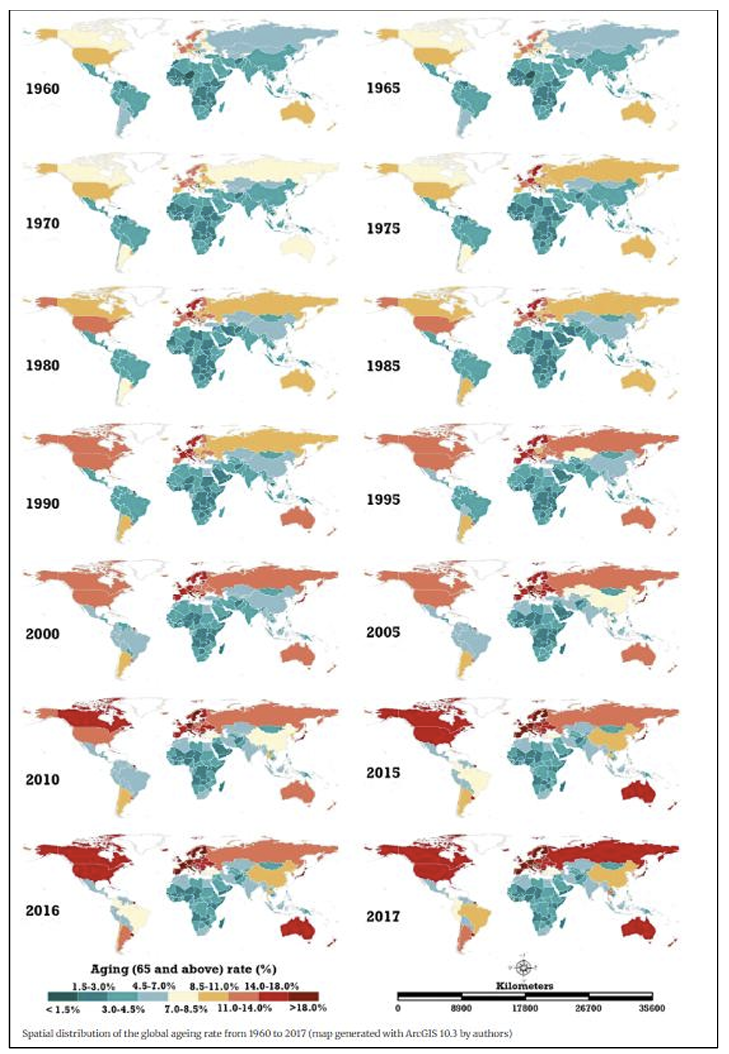

The ageing rates in 195 countries and regions all demonstrated a growth trend. Figure 1 shows the spatial distribution of the global ageing rate from 1960 to 2017. The number of countries and regions where the ageing rate is greater than 7.0% increased from 37 in 1960 to 91 in 2017. Moreover, the ranking of ageing countries changed during the study period. The top five highest-ageing countries in 1960 were Austria (12.15%), Belgium (11.87%), the United Kingdom (11.76%), Sweden (11.76%), and France (11.59%). In 2017, they were Japan (27.05%), Italy (23.02%), Portugal (21.50%), Germany (21.45%), and Finland (21.23%).

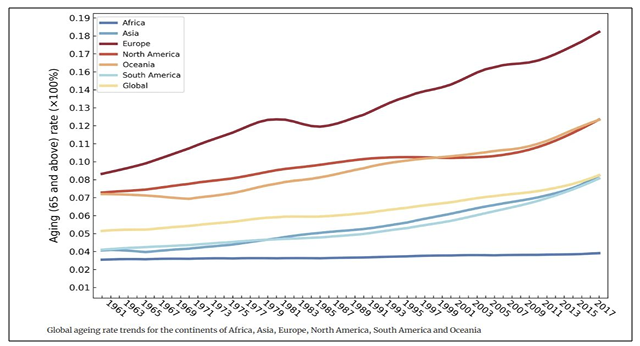

Figure 2 highlights global and continental trends in ageing rates. Among the six continents, Europe consistently had the highest ageing rate, while Africa had the lowest. From 1960 to 2017, significant increases were observed in Europe (0.1532%), Oceania (0.0873%), Asia (0.0834%), South America (0.0723%), and North America (0.0673%), with Africa showing only a slight rise (0.0069%). Since 2010, the ageing rate has accelerated on continents with higher ageing levels. By 2017, ageing rates reached 18.26% in Europe, 12.41% in North America, 12.40% in Oceania, 8.69% in Asia, 8.48% in South America, and 3.49% in Africa. Over the past 58 years, Europe, North America, and Oceania consistently maintained ageing rates above the global average of 8.70%, while Africa remained below it. Asia and South America, however, are closely aligned with the global average.

Obviously, the global problem of the ageing population is crucial to solve, and solutions have to be made.

2.2. Challenges of an ageing population

2.2.1. Effects on the economy

The first challenge is, slower economic growth, as the global population grows more slowly, especially with fewer people in the working-age group, the overall production of goods and services (GDP) might increase at a slower rate [1]. The productivity levels of the economy could decrease, leading to a decrease in the living standards of the people in the economy.

2.2.2. Effects on working adults

Another challenge would be the increased burden on working adults. They would have their children to take care of, if they have any, and they would have to take care of the elderly in their family. This would include providing financial support to them and providing time to take care of them. This could result in physical and psychological health problems for working adults [1].

The ageing population may create more career opportunities, particularly in healthcare, social care, and services catering to the elderly. There may be an increased demand for doctors, nurses, geriatric specialists, and home healthcare aides. As more people are getting older, the demand for professionals in the healthcare field will increase. The adults who may be unemployed may be able to obtain a job and increase their living standards.

2.2.3. Effects on wealthier economies and government

The third challenge could be the amplified economic effects of ageing in wealthier nations. In richer countries, the combination of ageing populations and existing economic patterns could intensify the financial challenges associated with supporting a larger elderly population [1]. As said above, there would be more pressure on the working adults. And the healthcare costs of the economy may increase. An ageing population may lead to increased government borrowing (public debt) to support the elderly, while individuals might save more (private assets) to prepare for retirement. This could also influence productivity levels.

2.3. Opportunities of an ageing population

2.3.1. Sub-saharan africa opportunities

The opportunity is an economic shift to Sub-Saharan Africa. While many regions face ageing populations, sub-Saharan Africa has a younger and growing population. This could lead to a larger share of the world's economic activities happening there in the future [1].

As these economies tend to have a rather younger population, their productivity would be higher. With this advantage, it may enable them to have a larger advantage in the global trading market, and the average costs of production would be lower as massive amounts of goods are produced.

As today’s middle-aged and internet-savvy population moves into old age, they will create a growing market for online-based services and support. An ageing population also presents opportunities for the growth of the medical and pharmaceutical sectors in the UK as the demand for new drugs and health treatments continues to rise [5].

Also, the ageing population may be able to provide business opportunities and may be able to push the economic growth of the economy to a faster pace [2]. The ageing population may be able to provide developing countries with an opportunity to experience an economic boom.

An interesting potential economic benefit of an ageing population is an increase in entrepreneurship, particularly for active older people who, while planning to retire, are keen to use retirement to explore new life opportunities. Even if older people are not interested in setting up their own business, they may be interested in the idea of investing in local businesses for financial reasons, particularly in the context of low interest rates. In addition, former business leaders who are retiring or scaling back their involvement could play an important role in supporting or mentoring future younger entrepreneurs who are starting in business [5].

There may also be changes in the type of infrastructure required in an ageing society. For example, the way society uses public transport may change with reduced pressure on commuter services as the working-age population decreases. Housing and services provision will also need to change, as people may decide to move out of highly populated areas to the suburbs and rural areas. This may provide opportunities for developers and the construction industry to explore new types of housing provision and communities to support older people and the wider community. The digital industry is likely to play an important role in these changes, helping to improve access to services for an increasingly internet-literate older population [5].

2.4. Effects on developed vs developing countries

2.4.1. Definition of a developed and developing economy

There are 3 different approaches to defining them. The World Bank considers any country with a Gross National Income (GNI) per capita of $12,536 or higher to be high-income and therefore developed. The others are developing countries as they haven’t yet reached this threshold, and are further subdivided into low-income (under $1,035), lower-middle-income ($1,036 to $4,045), and upper-middle-income countries ($4,046 to $12,535). This is the first way of defining whether a country is developed or not. The problem with defining a method is that there may be countries with high income yet are rather poor in many other ways. Another way of defining this would be the Human Development Index (HDI) of the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), therefore takes into account not only income but also health and education. The last way is the extent of industrialization of the economy. In this view, developed countries are industrialized countries. (assaj401,2022). For most cases, three approaches are valid in defining the ageing population; in this project, the definition would be the GNI per capita approach.

2.4.2. Effects on a developed economy

Developed countries tend to have longer life expectancies, due to better medical care and higher quality of life. This would mean that the percentage of the population that is in the elderly age would be a larger proportion than that of a developing country.

As people age, they tend to have more health issues, which leads to higher healthcare spending. Governments and individuals will need to spend more on medical care, long-term care, and medications. This can strain public health systems, leading to higher taxes or cuts in other services to cover the costs.

With a higher proportion of older people, there may be fewer people of working age (usually 18-65). This can result in a smaller workforce, which can slow down economic growth because fewer people are working and producing goods and services. There may also be skill shortages in some sectors as experienced workers retire. The productivity of the economy may decrease. Older people are more likely to rely on pensions and social security for income. As the number of retirees grows, the government may need to spend more on these benefits. This could lead to higher taxes or a need for pension reforms to ensure that the system remains financially stable.

2.4.3. Effects on a developing economy

Younger populations typically drive economic growth through their participation in the labor force, entrepreneurship, and consumption. As the population ages, there may be a shrinking working-age population, which can reduce the country's overall productivity and economic output. Developing countries typically have less investment in education and skill development for younger generations, economic growth could slow down, leading to lower incomes and reduced development potential. Many developing countries have informal or underdeveloped pension systems. As the elderly population grows, governments may struggle to provide adequate retirement benefits, especially in countries where social security infrastructure is weak. Without sufficient pension systems in place, older individuals may have to rely on family support or live in poverty, increasing the pressure on already struggling households. With fewer young people entering the labor force and a growing number of retirees, there could be labor shortages in key sectors like agriculture, manufacturing, and services. Developing economies often rely heavily on manual labor, which could be affected as the workforce ages and fewer young people are available to fill these roles. This could slow down industrial output and agricultural productivity, especially in countries that still rely on labor-intensive sectors.

3. Discussion/ development

Within this discussion section, the effects on the labor market, government, and whole economies would be analyzed.

3.1. Labor market effects

3.1.1. Declining workforce participation

Declining labor participation in the economy would lead to multiple issues, such as declining production and a decrease in economic growth. The declining workforce would lead to bad outcomes and cause issues.

A case study in Italy could be used to illustrate this issue. Italy, one of the fastest-ageing countries in Europe, has one of the oldest populations globally, with trends driven by both declining fertility and increasing life expectancy. Italy's birth rate is among the lowest worldwide, at just 7.6 per 1,000 people (World Bank). Italy also has one of the lowest labor force participation rates in the EU, with 48.7% in 2019, compared to the EU average of 57.3%. Female participation is especially low at 39.9% versus 58.1% for men [3].

Governments can try to use policies to mitigate these issues by changing immigration policies, increasing fertility rates, and encouraging women to enter the workforce. By increasing the labor participation among women, the economy could be able to increase its production of the economy by a large proportion. Women tend not to participate in production due to their identity as housewives, where they take care of children and do housework. Another reason could be the discrimination faced by women in the labor market, as employers may tend to believe that women would not produce the same productivity. Women may face discrimination due to their biological needs, such as pregnancy. This would mean that they would have to take off for at least 3 months to prepare for the upcoming new baby, and this may decrease their working hours. The government could impose policies such as setting laws to stop companies from discriminating the female workers in ways such as giving lower wages to female workers than male workers. By enforcing the labor market to allow women to be treated equally to men, the productivity gap caused by an aging population in the economy can be decreased.

Immigration policies would mean decreasing the requirements for immigrants to be able to settle in the country. This may be able to increase the young people in the labor force, as the immigrants who choose to come to a country would usually be the youth who seek opportunities in a new environment to make more money. By doing so, the economy would be able to decrease the gap caused by an ageing population, and more young blood entering the labor market would allow production to increase in the economy. The government would set a policy where skilled workers could have visas if they came to work in the country and set requirements for the definition of a skilled worker. By doing so, the government could encourage those with skills to provide the economy a boost in growth to come and work in the economy and discourage those who a relatively not skilled from entering the economy, increasing pressures on the environment.

Low fertility rates are also one main factor that leads to an ageing population in an economy. This indicates that the new domestic blood that enters the labor market would be low, there would be fewer babies, meaning the workers in the future would decline. The government can provide subsidies to families with more than one child, as the cost of raising a child is the main reason for low fertility rates in economies, and providing subsidies could reduce the cost of doing so. Therefore, people would have more incentives to have babies. Another reason why the fertility rates are low could be the attitudes of society to having babies. The people in the economy could bear in mind that having babies is a waste of time, and would not want to have one, Governments could provide advertisements on social media in an attempt to try to change this kind of attitude.

3.1.2. Productivity decrease

With more and more people getting older in the economy, productivity will decrease as the elderly may not have the same stamina as the youth and may not be able to work for as long as the young. Also, they may possess outdated skills unsuitable for production in the modern economy. Their production methods may not be as efficient as the production methods in the modern economy, and therefore, they would not produce as much as the production methods do now. For example, an old worker who still uses production methods from the 90s would not be as efficient as a younger worker who uses the production methods in 2020.

Older workers would also have to face larger health costs, as they become older, the chances of them getting sick would increase, and this would cause the productivity of these workers to decrease as their working hours would decrease due to more sick leaves. For instance, the worker could have worked for 46 hours a week, where he/she could have produced 1000 units of goods; however, because of increased chances of getting ill and the increased sick leaves caused by this, the production of these workers decreased to 600 units a week.

Even though there are multiple problems caused by an older workforce, the issues can be offset by increasing the investment in skill development and education. By increasing skill development, the outdated skills of these workers (elder workers) could be improved to the updated skills, better for production in the modern economy. Spending more on education would have the same effect on improving the productivity of the economy, as skills would be up to date, and the production of the economy would be more efficient. Improving healthcare would be able to reduce the chances of elderly workers getting ill and therefore reduce the rate of workers asking for sick leaves, resulting in a productivity improvement.

3.2. Fiscal challenges and policy implications

3.2.1. Public debt and pension pressures

Higher dependency ratios would cause the pressure on healthcare and pensions to increase.

The increase in the elderly in the economy and they tend to get sick more often than those who are younger. This would result in a rise in the costs of providing healthcare to them and would lead to a rise in the pressure on the working adults in the economy, and could therefore decrease living standards. The public debt would rise as there would be more people to take care of.

With the increased number of old people, governments would have to give out more pensions as a result, the costs of pensions to the government would increase. This may be caused by people retiring but living longer, meaning the years they require pensions would increase, and therefore would lead to more costs. Governments would have to increase their taxes to maintain a balanced budget. This could result in decreased disposable income for the citizens in the economy, and could decrease consumption, which could decrease economic growth.

These problems could be offset by increasing taxes or pension reform.

Governments may have to increase taxation to fund the improvements of hospitals in the economy to meet the rising demand for healthcare. This would be fine in the short term, but the ageing population tends to affect the economy in a long-term manner, and this could lead to a long-term need for taxation and may result in a decrease in incentives for investment. This would thus lead to a decrease in the economic growth of the economy and could lead to cyclical unemployment (demand-deficient unemployment).

As mentioned, taxation would not be a good solution in the long term and pensions would require even more financial support. Governments could provide pension reformations to reduce the pressure on the financial requirements in the long term.

A case study of Sweden has provided an approach to pension reformation.

Sweden has been proactive in addressing the fiscal challenges of an ageing population, particularly through pension reforms in the 1990s in response to slow economic growth and rising ageing costs (Sweden Ministry of Health and Social Affairs, 2016). The Swedish pension system includes a Notional-Defined-Contribution system financed on a pay-as-you-go basis, with an 18.5% contribution rate split between employers and employees. A buffer fund ensures that when contributions fall short of benefits, the fund covers the difference [3].

However, this would require a long period for the policy to be effective. Pension reformation would require the government staff to approve this proposal and there would be a lot of paperwork that has to be done which would increase the costs in the process. After the policy has been approved, more people may be retired, and the policy may not be as effective as predicted.

The government would have to reduce the paperwork needed to approve these kinds of policies and increase the efficiency of doing such work. The government could, for example, provide a system where policies such as improving the government’s budget or increasing social welfare, authorities could vote to approve the proposals.

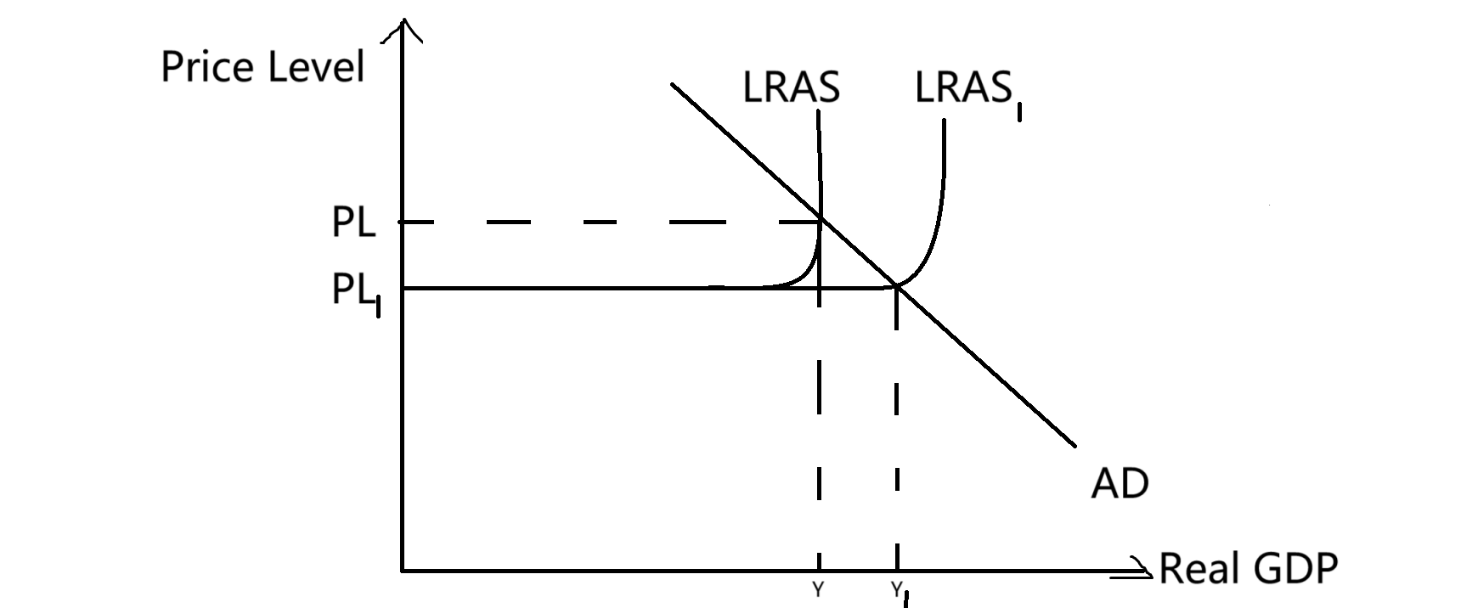

3.2.2. Structural unemployment

As mentioned before there may be structural unemployment because of the changes in the production pattern in the economy and the elderly may not be able to keep up with the new skills in the present economy and may decrease the production potential of the economy. Governments could provide retraining campaigns to mitigate the effects of the structural unemployment brought by workers having outdated skills. The retraining programs can allow workers to suit the economy better and would increase the aggregate supply in the long run. As shown in Figure 3, the Long-Run Aggregate Supply (LRAS) would shift from LRAS to LRAS1 therefore decreasing the price level from PL to PL1 and the GDP of the economy would increase from Y to Y1. This may result in an increase in the living standards of the people in the economy due to lower living costs, and the happiness of the people in the economy would increase.

3.3. Decrease in production and solutions

As the population gets older, production will decrease as they may have less stamina to work for longer periods, and the economy's productivity may decrease as a result. The elderly will ask for more sick leaves, and this can lead to decreased production in the firms in the economy. The profits of the firms may decrease as a result, and they may decrease investment due to a decrease in retained profits and leading to a decrease in economic growth in the economy.

Immigration policies would be a solution to the issue. Governments could set policies such as a free work visa for those who are skilled and want to come and work in the country. This would be able to encourage those with the skills to provide the economy a boost in its growth and therefore, raise the living standards of the people in the economy. Governments may be able to earn more tax revenue and use it to invest in infrastructure in the economy. Firms may be able to hire skilled workers, which could lead to decreased costs of production as they may need to use fewer resources to produce the same amount of product. Profits will increase, and investment may increase, with the increased government spending, and the economy may be able to experience growth.

Increasing the retirement age would allow workers to work for a longer period and therefore increase production in the economy. workers would have to work for a longer time, which would force production in the economy to increase. However, this may cause the people in the economy who were about to retire to get angry. This is like, for example, you were about to get to the shore by swimming 3 kilometers, but some random person came and took you back to your halfway point.

The government may have to provide some benefits to the party mentioned in the latter paragraph to reduce their anger and prevent a strike that may damage the economic growth of the country. The benefit could be extra pay for this party or providing them with some discounts for their purchase of medicine. The spending of this party on medicine and healthcare would be large, and providing them discounts would be able to reduce the chances of them starting a strike.

If the government increases its investment in healthcare in the economy, the prices of healthcare may not be too high, and the life expectancies of the people in the economy would increase, and the policy of increasing retirement ages would be able to be effective. Additionally, the government can encourage preventative healthcare, which means telling the people in the economy to pay more attention to their healthcare when they are younger, and would reduce the need for money to pay for their healthcare when they are older. This would also be able to increase the working hours of the workers of the economy, as this would mean that there would be fewer sick leaves in the economy, and the production would increase.

3.4. Effects on developing economies and developed economies

As mentioned in section 2.4.2, a developed economy usually has more resources and more money than a developing economy to cope with the ageing population issue. Therefore, it would mean that the developing economy could impose supply-side policies such as increasing its investment in capital and technology in the economy, and this would be able to increase both the country’s production and the production potential in the long term. Also, the government could impose a policy to encourage workers in the country to prepare their pensions for the future. This would be able to eliminate or reduce the need for higher taxes for older people in the economy. Therefore, the productivity of the economy may not be harmed, as if higher taxes are imposed, the incentives for people in the economy to work may decrease, as they would have less income compared to the time before the rise in taxes. And this may lead to a decrease in their living standards in the future.

As for developing economies, they would usually have a larger potential for economic growth than developing countries, as developing countries have, in all aspects, met their maximum capacity and would have little space for improvement. Developing countries may be able to get foreign investment from other countries and could be able to learn some ways of formalizing their pension systems, and governments would, therefore, be able to allocate money more efficiently and could use the money left to improve the country’s infrastructure. This could increase the job opportunities for the people in the economy, and the unemployment rates of the economy may drop, meaning that more people may have better living standards.

3.5. Future economic adaptation

The government would have multiple ways of approaching the issue of the ageing population, such as providing retraining programs to those who have outdated skills and immigration policies mentioned before.

By retraining those with outdated skills, the unemployment rate in the economy may be able to be decreased, and this can lead to economic growth in the economy and may solve the production gap caused by an aging population in the economy. The government may have more tax revenue to give to the retired in the economy, resulting in a reduction in the fiscal pressures for the government.

With immigration policies that are more friendly to foreigners with high skills, more and more young and able workers may immigrate to the economy. This can also solve the issue of a production gap in the economy, as these workers would be more productive than the majority of workers in the domestic economy.

The economy would have to adapt to an economy that has been prepared to face the impacts of the aging population and have solutions if it has already happened.

3.5.1. Firms' adaptation in the economy

As mentioned above, the increase in the overall age of the economy would lead to a decrease in the production of the economy, and the firms could prevent their production from decreasing dramatically by employing more women labor in the company. Since the participation of women workers would be low in a typical economy, recruiting women workers could fill in the production gap caused by the large retirements of workers.

Another way firms can adapt is by increasing their investment in technology, as technology won’t get tired, it can produce every day and every hour, and this can allow the firm to require less of workers to produce and would potentially decrease their average costs of production. For some firms, it may require the workers to work with the technology to produce in the company, and could provide training to the workers in the company to better suit the newly invested machinery. For example, a firm in the economy may need labor to work with the capital to produce, and it would have to give the labor training or some time to get familiar with the new machine.

Overall, even though there are multiple issues with the solutions of the government it could fix them with policies in the economy. And the firms in the economy may be able to adapt by increasing female workers in the company and improving technology.

3.6. Case studies

This section will looking into two separate case studies exploring the impacts of an ageing population on a country's economy. Within each case study, it will explore the extent of the impact of the ageing population on the economies of these countries.

3.6.1. New Zealand

The report by Melissa van Rensburg, Shane Domican, and Andrew Kennedy from the New Zealand Treasury examines the economic implications of New Zealand’s ageing population, driven by declining fertility rates, increasing life expectancy, and migration trends. Fertility rates have fallen below replacement levels, influenced by higher female workforce participation, education, and delayed childbearing. Meanwhile, life expectancy continues to rise, leading to a growing proportion of elderly citizens. While immigration partially offsets ageing by introducing younger workers, its long-term impact is limited due to migrants’ eventual ageing and global demographic shifts. By 2070, individuals aged 65+ are projected to comprise over 25% of the population, reshaping labor dynamics and economic demands.

Labor supply is expected to decline as older populations participate less in the workforce and work fewer hours. Despite rising participation rates among women and older workers, projections indicate a cumulative 6.1% drop in aggregate labor force participation by 2073. Productivity may face mild declines due to age-related cognitive changes, though experience, technological adaptation, and capital investment could mitigate losses. Wage profiles suggest older workers earn less than prime-aged counterparts, but demand for skilled labor in a shrinking workforce may elevate wages overall.

Capital markets may see shifts in savings behavior, with retirees drawing down assets, potentially raising interest rates over time. Housing and asset prices could face downward pressure as elderly populations downsize, though global capital flows and policy responses might alter outcomes. Demand-side effects include increased healthcare spending and reduced education needs, altering sectoral productivity. Sectors like health and aged care may expand, while education and manufacturing could contract, influencing aggregate productivity trends.

Fiscal pressures will intensify due to rising pension and healthcare costs, necessitating policy adjustments such as higher taxes, delayed retirement ages, or productivity-focused reforms. While ageing may slow GDP growth by reducing labor supply and productivity, technological advancements and human capital investments could counteract these effects. The report concludes that while ageing poses significant fiscal challenges, its economic impact can be managed through strategic policies, emphasizing adaptability and innovation to sustain long-term well-being.

3.6.2. Taiwan

A study by Wen-Hsin Huang, Yen-Ju Lin and Hsien-Feng Lee investigates the economic implications of Taiwan’s rapidly aging population, utilizing quarterly data from 1981 to 2017. Taiwan’s demographic transition is notable: by 2026, it is projected to become a “hyper-aged society,” with over 20% of its population aged 65 or older—a shift occurring faster than in many advanced economies, including Japan and the United States. The analysis reveals two contrasting trends. First, the aging workforce—specifically workers aged 55–64—exerts a significantly positive influence on economic growth, likely attributable to their accumulated expertise and institutional knowledge, which enhances productivity. Second, the rising Old-Age Dependency Ratio (OADR) demonstrates a negative correlation with economic growth, primarily due to diminished Total Factor Productivity (TFP) as fewer working-age individuals support a growing retiree population. This imbalance underscores structural challenges in sustaining output amid demographic shifts.

The study reconciles conflicting literature by highlighting Taiwan’s unique context. While prior OECD research often associates aging workforces with productivity declines, Taiwan’s older workers contribute positively, suggesting that experience and skill retention can offset age-related limitations. However, the negative impact of OADR emphasizes the urgency of policy interventions. Initiatives such as Taiwan’s “Long-Term Care 2.0” program, which expands community-based eldercare, and the integration of foreign labor mitigate caregiving burdens and labor shortages, thereby alleviating pressure on domestic productivity. Furthermore, human capital development, particularly higher education attainment, emerges as a critical driver of TFP growth, enabling older workers to innovate and mentor younger cohorts.

The authors propose multifaceted policy reforms to address these challenges. Key recommendations include: (1) implementing flexible retirement schemes to retain experienced workers, (2) enacting anti-discrimination legislation to promote elderly employment, (3) restructuring pension systems to ensure fiscal sustainability, and (4) prioritizing healthcare and social welfare programs to support aging citizens. These measures aim to harness the productivity of older demographics while addressing the economic strain of a shrinking workforce. By strategically balancing demographic realities with institutional reforms, Taiwan could transform the challenges of population aging into opportunities for sustainable growth.

4. Conclusion

Population aging is a deteriorating global issue that transforms the nature of economies. Improved life expectancy and falling birth rates have made the old more populous than the young. The shift has implications and opportunities for all countries in the world. The article here looks at how population aging influences a country's economy, through the analysis of global trends, case studies by region, and the means to cope with such change.

One of the key issues is the reduction in economic growth. As the dwindling young workforce, so too are the numbers of people who are making goods or providing services. This can make the size of the national economy, as measured by Gross Domestic Product (GDP), shrink, which affects people's standard of living. In wealthy countries, this is a serious matter because the labor force is reduced. Older employees might find it difficult to learn new technology or conduct strenuous physical work, making it more difficult to keep up with normal functioning. Additionally, adults in their twenties, thirties, and even forties tend to have to take care of both children and older parents. This extra responsibility can tire them out and make it tough to focus on work. On top of that, governments—especially in wealthy places like Sweden—spend more on healthcare and pensions for older people. This can mean higher taxes or more debt, which could cause money troubles later.

Even with these challenges, an ageing population can bring some good opportunities. In areas with lots of young people, like parts of Africa, businesses might move there because workers cost less. This can help these regions grow stronger. In places with more older people, there’s a bigger need for products like healthcare, eldercare services, and products made for seniors. This demand can create jobs and help certain businesses thrive. Plus, the elder can pitch in by starting companies or teaching younger people what they know, which can spark new ideas and keep the economy moving. These possibilities show that an ageing population isn’t just a problem—it can lead to positive changes if handled smartly.

Different countries deal with ageing in their ways. Wealthier nations, like New Zealand and Taiwan, have plans to adapt. New Zealand brings in younger workers from other countries, though those workers will get older eventually. Taiwan helps older people keep working and builds better care systems for them. Poorer countries, with less money to spend, might focus on education or invite companies from abroad to help. Each place needs a plan that fits its own needs and resources.

Technology and new rules can make a big difference. Machines and intelligent systems, like robots or artificial intelligence, can do some of the work when there aren’t enough people. Training programs can teach older workers new skills so they can stay in their jobs longer. Governments can also change things like the retirement age or how pensions work to save money. Spending on healthcare can keep people healthier, too. These steps can ease the pressure and make life better for everyone.

In the end, an ageing population shakes up economies in tricky ways. It puts stress on workers and government budgets, but it also opens doors for growth. Countries like New Zealand and Taiwan prove that good ideas can turn challenges into wins. By using technology, updating rules, and supporting people, nations can build stronger economies that work for all ages. The extent to which an ageing population would impact a country’s economy would not be large and negative with good planning.

Future research can be done on the discrimination women may face in the labor force, and the quantity of productivity they may bring to the economy. Additionally, more data from different countries would have to be obtained, as the countries chosen in this paper may be a good example, but cannot represent the global economy.