1. Introduction

Political participation is regarded as a basic human right in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights [1]. Given the fact that women constitute half of the world's population, democracy cannot be achieved without their participation. Introducing more female politicians into government positions has an influence on political agendas, potentially urging the government to concentrate more on the welfare of women and children, and uproot discrimination against them. Therefore, the international community, governments, grassroots organizations and individuals have been making efforts to promote gender parity in politics. As early as in 1952, the United Nations passed the Convention on the Political Rights of Women, which emphasized that men and women have equal rights to take part in government. However, according to UN women 2021 statistics, the reality is that in average, women only represent 25.5% of all parliament members, 21% of all government ministers and 5.9% of all heads of states [2]. Women are underrepresented at all levels of decision making worldwide, including in the highest positions of national power. Thus, the presence of a female president receives global attention, lauded as a major moment in the process of achieving gender equality in politics. Academic scholars have also taken interest in the success of these women and their unique career paths to understand their success, public response, and give new ideas to the next steps in female political promotion.

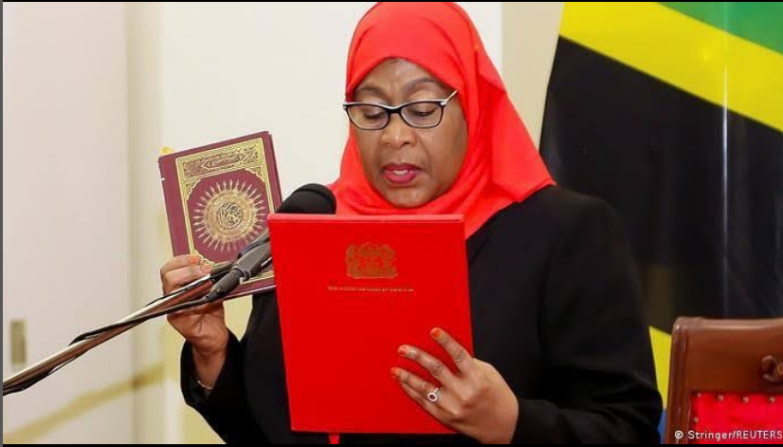

Samia Suluhu Hassan, a 62-year-old female politician from Zanzibar, United Republic of Tanzania, took office as the sixth president of the United Republic of Tanzania on 19 March 2021 after the death of president John Pombe Magufuli. She is the first female president in Tanzania. According to the Tanzania constitution, the country's vice president will become president of Tanzania automatically if the present president is absent during presidential terms [3]. Although her presence in presidential office is sometimes considered accidental, as she was not voted into office, it is undeniable that there are many highlights in her career path worth discussing [4].

In reviewing Samia's full career path, her success in the 2010 general election for constituency seat was the turning point in her career as this position let her perform more important and prominent roles in the government. In this article, I critically examine the reasons for Samia's electoral success. Drawing from research on Samia's public speeches, policies and reports on social context in 2010, I argue that Samia Suluhu's electoral success is largely due to her charisma and attributes, as well as the broader social context, whereby women were encouraged to take on new roles in society. Lastly, local politics and civil unrest in Zanzibar instigated a social consensus on the need for a new leadership style, that Samia offered.

This article will start with an introduction of Samia's personal background, and then review literature on barriers, and opportunities, for female to participate in and occupy political positions. I will use the theories and models mentioned in the literature review to analyze her electoral success, taking both her personal factors and the broader context into consideration. These theories and models include Conger-Kanungo model for measuring charisma, and contingency model which link successful leaders to the specific social context which they live in.

2. Brief Background of Samia

Samia Suluhu Hassan was born into an ordinary family in 1960 in Makunduchi, an ancient town on the southern tip of Unguja island, Zanzibar. Her mother was a housewife, her father was a school teacher. During her early life as a student, Samia never stopped studying. She first obtained an advanced diploma in public administration from the Institute of Development Management in Tanzania. She continued her studies abroad in England, where she earned a post-graduate diploma in economics from the University of Manchester.

Before running for a political position, Samia was a social activist. She participated in various grassroots institutions and non-government organizations and worked closely with local people. In 2000, her political career began. In one of her speeches, she stated that it was when she saw the conflict between the two parties in Zanzibar and how members in parliament neglected people's welfare then she decided to participate in politics [5]. After being elected to be a special seat member in the Zanzibar House of Representatives, Samia was then appointed by the president of Zanzibar to be the Minister of Ministry of Tourism, Trade and Investment and later Minister of Labour, Gender Development and Children in Zanzibar, becoming the only female member in the cabinet at that time.

Figure 1: Samia sworn in as President. Via from Samia's personal instagram.

Figure 1: Samia sworn in as President. Via from Samia's personal instagram.

The 2010 General Election was the major turning point of her political career. At that time, she was the only female candidate running for a constituency seat representing her hometown Makunduchi, a position that was traditionally occupied by men. Yet, she won more than 80% of votes and was highly successful in the election. Since the 2010 election, Samia was gradually appointed to increasingly take charge of key affairs and stepped into the center of the dominance party CCM (Chama cha Mapinduzi), successively serving as Vice-Chairman of the National Assembly and Minister of State for Union Affairs. In 2015, John Pombe Magufuli from CCM selected Samia as his running mate for the Union presidential candidate. After Magufuli won the election, Samia became the Vice-president according to Tanzania's constitution, making history for the first time a woman being appointed as the Vice-President of Tanzania government.

Stepping into the constituency seat in 2010 provided Samia with more opportunities and attention, thus paving the way for her future political success. By examining Samia's success in the election for this seat, this article aims to offer insight into her successful election experience, and recommendations for other female politicians' reference.

3. Literature Review

In countries with a parliamentary system, gaining support in general elections is the most basic and direct way for people to participate in politics. To increase the proportion of women in parliament, we should have more women running and winning elections. The following section will review literature focusing on two major questions: why women perform badly in electoral politics; what are the feasible approaches for female candidates to win elections and achieve political success. To answer these questions, I reviewed academic literature, with a specific focus on African studies and Tanzania, which analyze female political participation from political, sociological and psychological perspectives.

3.1. Barriers and Obstacles

Scholarly research provides extensive documentation trying to identify reasons for women's poor performance in electoral politics. According to the constitution of Tanzania, the political party should propose the candidate before running for the constituency seats. Scholars who focus on political system of Africa and Tanzania examined the electoral patterns and political parties' nomination logic. Through extensive field research, authors of the report entitled, Women and Political Leadership: Facilitating Factors in Tanzania argued that a winner-take-all system in Tanzania hinders women's participation [6]. Political parties in a winner-take-all system prefer to nominate male candidates because men are supposedly more loyal to their party and they are more capable of safeguarding party interest in the parliament. Since political parties need strong and persuasive candidates in parliament to stand by, they tend to nominate male candidates to run for constituency seats and then enter the parliament as their solid supporters. Therefore, women are usually at a disadvantage institutionally in the electoral process.

Scholars who study the social culture and norms viewed women's underrepresentation in government from a different perspective. When running for a seat representing a constituency, a candidate needs to spend time travelling through local districts and making speeches to the public. However, traditionally in Tanzania, the dual role of wife and mother is the most important [7]. Domestic affairs bring women heavy family burdens, limited financial resources and time, poor education, and capacity, etc [8-11]. Thus, most women have no time and funding to run for election.

Another key argument made by academics is that voters do not trust female candidates because of the gender-role stereotype. Findings in management studies stated that there is a mismatch between feminine qualities and the qualities commonly associated with leaders. In Schein's empirical investigations from 1989 to 1994, people perceived that the characteristics associated with successful leaders were more likely to be held by men than women [12,13]. Therefore, people are more likely to "think manager-think male". In the political field, "masculine" characteristics are perceived as more important than"feminine" characteristics in evaluating the effectiveness of political officers [14]. In addition, if women show masculine features they will be misunderstood and even hated because they are staying away from traditional roles and characteristics, thus they are in a dilemma [14,15].

From a psychological perspective, women themselves have somehow internalized these stereotypes psychologically [11]. In research interviewing women in Tanzania, Said Salim Ali found that women themselves do not have the courage to speak in public and they tend to not vote for candidates of their gender [16]. A quote from one of Ali's interviews reflects this ---"We women are so many, but we are not supporting each other. This is because still people think that women are not fit for political positions". Moreover, they tend to underestimate their knowledge and abilities in areas that are deemed "masculine" since they lack the confidence to compete with the other gender [17].

In conclusion, women themselves do not have willingness and other objective supports to participate in politics. The current political system is still male-dominated, which means female politicians are less nominated because of gender stereotypes. Lastly, social stereotypes on gender roles are a major barrier for women's political engagement.

3.2. Feasible Approaches to Win Elections

Although women face social obstacles in getting elected, there are still many examples of women being successfully voted into politics. Hopefully this literature will also figure out more facilitators for women's political advancement. Previous research has analyzed why these breakout cases were successful. Initially, literature on female leadership studies discussed that it is when women imitate masculine characteristics, that they are more acceptable as leaders [18,19]. Other scholars argued that women enjoy an advantage by performing certain feminine characteristics, to name a few, being cooperative, collaborative, friendly, expressive, people-oriented and socially sensitive [15,20,21]. Today's literature generalizes certain characteristics to become personal charisma and developed Conger-Kanungo model to measure it [22,23]. stating that personal charisma is a major contributor to one's electoral success [24,25]. However, research which primarily focuses on political leaders' characteristics cannot explain all cases. Therefore, other scholars took the broader structural, social, political, historical, cultural and institutional context into consideration. As early as 1964, Fiedler raised the "contingency model", which suggests that successful leadership depends on a match between leader characteristics and features of the situation that any leader confronts [26].

Literature then tests the "contingency model" under a circumstance of crisis. Research on management studies showed that female leaders were preferred when company performance was declining, whereas male leaders were preferred when company performance was improving [27]. Political Science literature The Role of Gender Stereotypes in U.S. Senate Campaigns demonstrated that female candidates get more votes when people believe a government is under stress and turbulence [28]. This was because under such circumstances the established gender stereotypes turned into advantages for women. To be more specific, women were viewed as more honest and more caring than male, being competent at dealing with social issues and relieving the tension. It was interesting that the research result also showed that women were even considered more competent in dealing with economic issues, which was stereotypically a male dominate sector.

According to literature reviewed above, the criteria for judging a politician is becoming verified and people's attitudes towards women's political participation is changing positively. A successful politician should not only have certain favourable characteristics, but the leaders should also be attuned to the social needs of their constituents and they should publicly make efforts to meet these need.

This section reviewed literature analyzing institutional, social and psychological factors that hinder women's political participation, and then present articles arguing decisive factors for women's electoral success. Through literature reviewed above, we can conclude that electoral success can only be gained with both personal charisma and contextual advantages. However, this pattern for electoral success has not been examined with the example of a specific female politician. Therefore, my research expands this literature by applying these observations to the context of Tanzanian culture and environment, using Tanzania's female president, Samia Suluhu Hassan, as key case study. The following section of this article will focus on Samia's personal charisma, then the border social context she faced, and finally discuss whether her features are accordant with social needs based on the contingency model.

4. Personal Charisma and Attributes

Charisma is proven by academics to be a significant part of leaders and leadership success. Max Weber is among the first academics to conceptualize charisma as: “a certain quality of an individual's personality by virtue of which he is considered extraordinary and treated as endowed with supernatural, superhuman, or at least specifically exceptional power or qualities”. Through showing these qualities, charismatic leaders persuade followers that he or she is trustworthy and admirable, capable of satisfying their followers' personal needs as well as guiding them to a common future [29]. In most democratic countries, voting is the main method to elect competent candidates in political positions. Voting behavior is a means for expressing voters' approval or disapproval of the qualities of the candidates who will be the representatives of them [25]. Personal charisma has a positive effect on voting behavior [25]. Reasons vary from increasing voters' political identification, arousing specific emotions, winning followers' trust etc. [30,31].

The analysis in this section builds off of Weber and theories of charisma's linkage to voting behavior in order to examine Samia's electoral success. In the introduction section, I stated that Samia won more than 80% of all votes in the 2010 election for Makunduchi constituency. I argue that one reason for Samia's electoral success was that she demonstrated personal charisma to the public through her public speeches, policies and appearances, which helped her earn more votes from followers.

To identify how Samia presented her personal charisma, I used the Conger-Kanungo model of measuring charisma. Conger and Kanungo developed a system which consists of three stages, including the assessment stage, the vision formulation stage and the implementation stage. After that he also designed 25 detailed descriptions on charismatic behaviors and features, which is also called the C-K scale, to further explain the three stages. Due to the fact that documents on Samia's personal speeches in 2010 election and her early policies were nearly impossible to find on the Internet, more recent speeches were analyzed. I chose 22 official speeches released by the government of Tanzania and other related reports and news to assess whether Samia's performance is consistent with Conger-Kanungo model.

The assessment stage requires charismatic leaders to be sensitive to the environment and focus on people's needs [32]. Specifically, leaders are expected to figure out the constraints hindering them to achieve organizational goals, both socially and culturally, technically and economically. For another, they always pay high attention to and clearly express their concerns for the physical needs and emotional feelings of organizational members or their followers [32]. In analyzing Samia's speeches, it is evident that she takes advantage of the assessment stage as she always shows her concern for specific barriers in different sectors facing her audiences, with a pragmatic speaking style. For instance, in her new year's speech of 2021, Samia chose to directly speak of the current constraints for macro development, including economic slowdown, damaged transporting infrastructure and difficulties in the promotion of some programs. She linked the Covid-19 pandemic with negative growth in economy, industry, agriculture, tourism and other public sectors. The impact of Covid-19 was denied by her preceding president John Pombe Magufuli, who insisted that there was no need to detect the virus and get vaccinated.

Furthermore, given the needs of different groups of people, Samia held several speeches on different subjects and communicated with targeted groups to tackle their problems accordingly. In her speech targeted at youth, Samia showed that she fully understood them by highlighting their concerns, including high unemployment rate, poor education quality and literacy rates, lack of financial support, negative environment for start-ups, etc.. She made the argument that her government is familiar with these issues by referring to detailed data, for instance the total percentage of unemployment young labour forces. Samia also held speeches especially intended for older generations, women and workers, pointing out their concerns respectively, such as a lack of women in decision making positions, medical difficulties, water security and etc.. Through these details in her speeches, Samia demonstrated that her leadership and government completed adequate research and are fully aware of social problems, thus enhancing followers trust in her. Due to these tactics, Samia has done well in the assessment stage.

In Samia's speeches, the assessment stage is closely linked to the implementation stage, and she implemented exactly what she committed in her speech. The implementation stage was initially defined as “assuming personal risk and engaging in unconventional behavior to reveal their extraordinary commitment and uniqueness” [32]. However, Samia took a different approach where she did not assume personal risk but still demonstrated extraordinary commitment. She showed schedules and achievements on problem solving once she raised a problem in her speech. She uses examples which are particularly persuasive and made people believe in her commitment to helping them in their life. For instance, in the speech targeted at women in the Tanzanian capital city, Dodoma, Samia promised to empower women and provided clear evidence of the government's progress under her leadership. Examples of this progress include that the appointed women in politics constitutes 46% of all administrative secretaries and 34% of all judges; private sectors have launched projects to develop women's working skills; the government has continued to build infrastructure for education at grassroots level. Moreover, she also demonstrated to the public that she is an unconventional leader by adapting milder attitudes towards opposition party. She made history after meeting with the leader of the main opposition party CHADEMA, which was the first time in Tanzanian history. Overall, Samia is committed to serving her people and successfully showed her commitment and uniqueness to the public through speeches, thus doing well in the implementation stage,

The final stage is the vision formulation stage, which is defined as “the ability of a leader to devise an inspirational vision and to be an effective communicator” [32]. Compared with specific approaches, the vision formulation stage requires charismatic leaders to be inspirational by expressing the vision for a common future and thus motivate his or her followers. Frequent expression of vision of a harmonious nation can be found in Samia's speeches. For instance, the new year's speech of 2022, speech for the Eid al-Fitr celebration ceremony of 2021, and the swearing-in ceremony all included her argument of “building a society with peace, justice, liberty and democracy”, a strong vision which delegates the heart-felt desire of Tanzanian people. From a rhetorical perspective, Samia always uses traditional idioms of Tanzania to emphasize the common value of all Tanzania people and inspire them. For example, Samia used “Umoja ni nguvu na utengano ni udhaifu”, which means unity brings strength and separation brings weakness; and “Ukitaka kwenda haraka nenda peke yako; lakini ukitaka kwenda mbali nenda na wenzako”, which means people should make joint efforts to achieve long-term success, so as to stimulate those who didn't catch up with the development of digital economy and encourage young people work together in business area. It is through these idioms that Samia makes her vision accepted by the local people.

After Samia was sworn in as president, she received a lot of praise and expectation from different groups of people, which also demonstrates her personal charisma, as she was liked by a wide variety of people. January Makamba, a member of parliament who once worked with her in the vice-president's office, stated that Samia's work ethic, decision-making and temperament shows that she is a very capable leader [33]. The general public show their respect for her by calling her “Mama Samia”.

In conclusion, Samia Suluhu Hassan performs well in the assessment stage, implementation stage and the vision formulation stage. She showed great sensitiveness to the social environment and people's needs, and demonstrated commitment to tackling social problems. She clearly stated the common goal for Tanzania society and stimulated his or her followers to achieve it. All in all, she successfully created a charismatic profile to the public and consequently influencing her followers' voting behavior. It is reasonable to conduce that her charismatic personality and attributes exhibited in her speaking style finally led to her electoral success in 2010.

5. An Encouraging Social Context

Personal charisma and attributes are not the only reason for one's electoral success in politics. The broader social context should also be taken into consideration. I argue that Samia's political success also reflected an encouraging social context, where Tanzania has made great efforts in promoting gender equality and encouraging women to take on new roles, especially political roles. Her electoral success showed that under such efforts, the traditional stereotypes of gender-role and women's “psychological glass ceilings” was diminished to some extent. People's attitudes, and women's attitudes toward the public positions of their own gender have been changing positively.

Traditionally in Tanzania, women shoulder the responsibility of agriculture and other domestic affairs, including washing, raising children and cooking [34]. They even held the leading position in some cases [35]. However, with the colonists introducing new institutions, ideas and economic patterns, women were gradually excluded from the male-dominated sectors in the colonies as in Europe, for instance, finance, politics, business and etc., and they were considered inferior to men [35].

Things started to change after Tanzania gained its independence. The process of achieving gender parity has been accelerated entering the 21st century. There are many “firsts” happening in both Tanzania and Zanzibar in terms of gender equality.In addition to that Samia Suluhu Hassan won the constituency seat in 2010, exactly the same year Anne Semamba Makinda took office as the first female speaker of the National Assembly of Tanzania. In 2007, Asha-Rose Mengeti Migiro, another Tanzanian women, was appointed as the deputy Secretary-General of the United Nations, making her the first African woman to hold an important role in a multi-national organization. All these examples remind us that Samia's electoral success was not a complete outliner, but was part of this larger trend and within this border social context.

Samia was raised in a period when the Tanzania government accorded priority to women's political empowerment and decision making. In 1970, women only constituted 3.5% of all parliament members. To increase women's representation, Tanzania introduced the quota system for women in parliament in 1985, and then amended the constitution in 2005 to set a bottom line stating women should make up at least 30% of all parliament members . Apart from domestic laws and regulations, international and regional conventions have been ratified and accommodated in the country's legal framework system. Tanzania changed its legislation in accordance with the requirement of the 1997 and 2008 Southern African Development Community (SADC) Protocol on Gender and Development, which set the goal respectively to include 30% and 50% of women in parliament. 14 Members of SADC in southern Africa agreed that the state parties should take the responsibility to empower women through upgrading their legal structure, launching awareness raising campaigns, and building their capacity. These efforts led to an encouraging result. The average proportion of women in parliament in SADC increased from 17.5% in 1997 to about 24% at present, which is higher than the global average of 19%. In Tanzania, the proportion in both the upper and lower houses increased from 16.4% in 2000 to 34.2% in 2010. In the Zanzibar House of Representatives, female members' proportion rouse even higher, from 30% to 40%. In addition, main political parties in Tanzania have also formulated regulations on encouraging women's equal rights in politics. For instance, the constitution of Tanzania's ruling party CCM (Chama cha Mapinduzi), the party which Samia serves in, wrote that there should be no less than four women among all fourteen members in the National Executive Committee [36]. These conventions, laws and regulations act as a strong foundation for women's political participation.

Around 2010, the year when Samia ran for political elections, satisfying outcomes can not only be identified through women's participation rate, but also people's general attitudes towards women's participation. According to 2008 Afrobarometer Survey, for the question “How well or badly would you say the current government is handling the following matters, or haven't you heard enough to say: Empowering women?”, “fairly well” constituted 48.6%, while “very well” constituted 17.8%,exceeding the average of 20 African countries [37]. In the 2005, Afrobarometer Survey, 87.8% of interviewees supported for women's equal rights. Meanwhile, 89.6% of interviewees agreed that women could also become leaders [38]. These statistics indicate that the government's firm attitudes towards women's political participation had a positive effect on people's recognition. More people agreed with the fact that women should have political rights, and a friendly social environment towards female politicians was created.

Apart from the broader social environment, the most prominent change happened in women's attitudes towards public positions of their own gender. Data from the National Electoral Commission of Tanzania shows that in 2005, women constituted 51% of all voters. Therefore, winning women politician's support was a key component of Samia's electoral success. As mentioned before, if women themselves don't believe that they can take on political roles, they would not compete for the leading position and even would not support each other. Under such situations, different programs helped women become aware of their political rights. In the Tanzania gender networking programme, there were 557 women contesting for seats in parliament in 2010, out of whom 190 contested at constituency level, compared to only 70 in 2005. In northern Tanzania, Women's Rights and Leadership Forums (WRLFs) held political forums for women [39]. One of the WRLFs program's members commented that”I know I am a leader. I am courageous and am now able to stand in front of men and say “you are the ones who are wrong”. Similar cases also happened in ILO's projects implemented in Unguja and Pemba Island, Zanzibar. A 45 year old women Sabina Mohamed Ali was then motivated to contest and win the position of Sheha (Administrative units in Tanzania) in 2004 [40]. 80% of women who benefited from Women Development Fund admitted that their self-confidence was increased because they could control their lives, and they had the feeling of ownership and success. Another project, the Women Empowerment in Zanzibar (WEZA) project (2008-2011), empowered 27 women to contest for the 2010 elections. It showed a drop in the data on women who do not dare to speak their idea in public from 28.7% in 2008 to 12.5% in 2011 [41]. More importantly, 70% of women feel that women should support other women in their campaign and vote for them, a dramatic increase compared to 16% (Unguja) and 9% in 2008. Women's psychological glass ceiling for political participation was gradually broken.

Based on the data provided, it is evident that a welcoming political environment for women can be seen both at international level, country level and grassroots level. Women were not only increasingly welcomed to political and leading positions, but also people's attitudes, especially women's attitudes towards taking a leading role were changing. It was under such circumstances that Samia gained more than 80% of votes in her community and was elected into political power.

6. Changed Social Needs in Conflicts

As the “contingency model” suggests, successful leadership requires leaders to adapt to the social context and meet followers' need. Female politicians who were elected since the beginning of 21st century as head of state or government so often appeared in periods of uncertainty, unrest and transition. Social transition offered a more inclusive political space opened for civil society and a greater freedom of press and speech was allowed [42]. Samia Suluhu Hassan's electoral success occurred during a period of similar uncertainty, where Zanzibar was on the eve of political reconciliation. I argue that Samia's electoral success was also due to the fact that her competence and personal charisma were consistent with Zanzibar's special social context and people's needs.

After being dominated by the ruling party Chama cha Mapinduzi (CCM) for such a long time, the introduction of multi-party system to Zanzibar was not a smooth transition. The elections of 1995, 2000 and 2005 witnessed different degrees of social and political conflict. The violence was extremely severe and caused a great loss of human life when the army and police attacked thousands of supporters of the opposition Civic United Front (CUF) in a rally in 2001. They also conducted a house-to-house rampage, indiscriminately arresting, beating, and committing sexual abuse towards Zanzibar residents [43]. It was when the ruling party CCM and the opposition CUF reached a consensus on building a national unified government that the situation improved. However, cases of intimidation were still reported in 2010 election. In 2010, 66.4 percent of the voters supported the proposal for a government of national unity when holding a referendum [44]. Although cooperation between CCM and CUF was finally reached, the social trauma caused by decades of political conflict still needed time to recover. During those years, the government and parliament's ability to solve practical social problems were severely restricted by partisanship [45]. Even people's basic daily needs and demands were neglected by the government. In local communities, political factionalism had destroyed the previously harmonious social relations. Supporters of the two parties would even avoid cooperating with supporters of the opposition party during important social events, such as funerals and weddings. The political conflict also violated basic human rights. People had no freedom to express their views, fearing that they would be punished by the police [46].

Samia Suluhu Hassan enjoyed so-called leadership advantages under such circumstances. When a society faces turbulence and crisis, people's requirements for leadership may be quite different from that of a peaceful community and women are usually more favoured [47]. One factor is that people believe that women are likely to provide a new direction in leadership and change the current situation . The discrimination against gender-role and traditional link between males and leadership is again diminished under such circumstances. Female characteristics, including being understanding, helpful, sophisticated, aware of the feelings of others, creative, and cheerful are considered to be more useful during these periods [12,13,48]. Moreover, women are thought to be good at consensus building and more competent at education, health care, children and family issues, and poverty than men, which are needed in these turbulent times. These stereotypes turn to become advantages for female leaders in a turbulent society [49].

Taking Samia's personal features into consideration, a strong connection can be seen between her competence, charisma and what her followers needed from political leadership during that period. Following Bandura's notion of proxy control, believing a leader's ability to tackle his or her followers' problems relieve followers of the psychological stress and loss of control created in the aftermath of a crisis [50]. According to the 2005 and 2008 Afrobarometer Survey in Tanzania, what people were most concerned about was water supply, health, poverty, infrastructure and education [37]. Therefore, they needed a capable and pragmatic leader who was familiar with these issues. Before being elected as a member of the House of Representative, Samia had abundant working experience in both non-government organizations and official departments. She worked for World Food Programme from 1988 to 1997, during which time she worked at grassroots level and directly dealt with food issues in her hometown community. She was also a member of Zanzibar Education Policy Development Committee and the founding member of the Tanzania Association for the Development of Development Women. These grassroots experiences brought a strong connection between her and the local people, as well as making her more credible to help solve social issues and meet people's need. After taking special seat in parliament, she was appointed to take charge of several ministries in the government, accumulating experience in the fields of trade, investment, youth development, employment, and women and children affairs. These grassroots and political experiences showed the public that she was a sophisticated, experienced leader and laid a foundation for people's trust in her competence.

Samia's public charisma, as seen in her speeches and policies to the public, also gave indication to the public that she is a capable leader and cheerful leader. I also argued that this charisma played a bigger role when being examined by people in this specific social context. Several characteristics that were mentioned the most in news and social media about Samia showed a great consistency with what people need during social turbulence and crisis. First of all, she “walks what she talks” [51]. In one of her interviews, when she was asked for her opinion towards those who do not believe women can lead, she said that the only approach to deal with stereotypes is “Implement the development plans and they will change”. As she mentioned in her interview, the reason why she decided to enter into politics was that when she saw a majority of people in Zanzibar struggle to access social services for example water, health and quality education, and that other government officers neglected these needs, she decided to participate and make a change. In 2005, as the minister of labour, gender development and children in Zanzibar, she overturned a ban on young mothers returning to school after giving birth, fulfilling her promises of equality in education. After becoming the president, she continued to hold conversations with different social groups in order to tackle their problems and meet their needs. Moreover, she is also said to be inclusive and good at consensus building, which can also be seen in her inclusive policy towards the opposition parties [51]. This kind of characteristics met the needs of Zanzibar society where there was tension among neighborhoods and the whole society. It was helpful for her to let people believe in her ability to bring peace to the community. Furthermore, Samia is a woman with candidness and firmness, who unhesitatingly introduces her policies. These are also characteristics valued under social turbulence and crisis, and are key reasons for her success in politics.

In this section, Samia's personal characteristics and the border social context were taken into consideration. Samia's electoral success is consistent with the contingency model, where leaders with characteristics that meet the social needs are proven to be more likely to gain their follows' supports.

7. Conclusion and Discussion

As the first female president in Tanzania, it is important for academics to assess Samia Suluhu Hassan's personal story and path to political success. In this article, I explored various reasons for Samia Suluhu Hassan, the present president of the Republic of Tanzania, winning of the constituency seat representing Makunduchi in 2010. Drawing from scholarship in leadership studies, I took both personal and contextual factors into consideration when analyzing Samia's electoral success. I discovered three main reasons for her high supporting rate. First of all, using the theoretical framework arguing that politician's charisma has a positive effect on followers' voting behavior, I found that it is her personal charisma and her successful presentation of attributes through public speeches that helped her gain more followers. I adapted the Conger-Kanungo model of measuring charisma and found that Samia successfully presented an image as an insightful, people-oriented, unconventional, pragmatic and inspirational politician. This means that her personal charisma was recognized by voters and positively impacted their voting behavior. Secondly, a changing social context also played an important role in empowering Samia and other females to participate in politics. After implementing domestic and international laws and regulations related to female political empowerment for many years, Tanzania has gradually formed a more welcoming environment for female politician. Research and programs done by different organizations all demonstrated the fact that voters' attitudes towards women as politicians changed for the better around 2010. Lastly, I considered Samia's success in a more specific social context, in which social unrest has long been a problem in Zanzibar. I argued that Samia's experience in grassroots organizations and different departments of Tanzania government, as well as her personal charisma, were in accordance with people's needs, and instrumental to her gaining support in 2010.

This article focused on one politician's experience, and tested several models in leadership studies in African political context. I analyzed extensive primary sources including Samia's speeches, people's comments on social media and newspapers, as well as other materials, for example program reports by non-government organizations. However, due to our inability to do fieldwork in Tanzania and interview local resources, the social context analysis was not precise to the constituency of Makunduchi. Materials around 2010 were also unable to be located. Further research can be done in this prospect, and the model used in this article could also be tested on other female politicians in Africa and in the whole world.

Although Samia's career path cannot be exactly mimicked as her success is based on a specific social and historical moment, the findings of this article still can serve as a reference for future female politicians. This research shows that what is considered important for a female political leader and what contributes to a higher voting rate. The findings of this article also provide an opportunity for us to reflect on the contributions made by Africa and the whole world towards women's empowerment. For organizations and government, even women themselves in Tanzania, since the reconciliation between parties is still considered as an important subject, this social context should be fully taken into consideration when thinking about how to further empower women in politics. Samia's story is ongoing, and we still need more research to understand this female politician and the ongoing political environment in Tanzania.