1. Introduction

Cambodia, positioned as one of the poorest nations in Asia, is facing numerous economic challenges [1]. Despite its shift from being classified as a low-income country to a lower-middle-income nation, the fragility of Cambodia's economic is multifaceted and complex. According to the report proposed by the World Bank in 2015, the subsequent emergence of Covid-19 led to an upward trajectory in poverty rates. Research projections suggest that compared to the approximately 18% national poverty rate estimated in 2019/20, the impact of inflation could potentially contribute to a 4-percentage-point increase in Cambodia's poverty rate [2]. The cause by the Cambodian government in 2018 is that the productivity in the country is negatively affected by multiple factors, including inefficient logistics systems, high transportation costs, and a problematic business environment characterized by irregular fees [3].

Historically, Cambodia has implemented various policies to address poverty-related issues. Between 1996 and 2005, the government initiated two successive Social and Economic Development Plans - SEDP I (1996-2000) and SEDP II (2001-2005). However, neither of these plans incorporated monitoring and evaluation to track their implementation progress. Following these, in late 2002, the government introduced the National Poverty Reduction Strategy (NPRS) for 2003-2005[4], which marked a significant step in Cambodia's poverty reduction efforts. Notably, within a year of its implementation, Cambodia witnessed a significant expansion in its garment industry, marked by a notable 27% increase in 2003. This surge played a pivotal role in driving growth across the manufacturing sector, which experienced a noteworthy rise of 12.2% [5]. In 2008, the Cambodian government extended the NPRS by three years until the end of 2013.

In parallel, Cambodia initiated the “Rectangular Strategy” in 2004, completed in 2018. This policy yielded positive economic outcomes, with Cambodia's recurring income doubling from $2.264 billion to $4.56 billion between 2013 and 2018 [6]. With the new appointment of Prime Minister Hun Manet in 2023, Cambodia has embarked on the first phase of the "Pentagon Strategy," a long-term plan set to continue until 2050, with the goal of reducing poverty to below 10 percent [7].

In the context of this ambitious target and considering the aforementioned challenges Cambodia faces, this paper begins by analyzing the challenges in the country's garment processing industry, highlighting its low value-added aspect. Subsequently, it proposes that promoting basic and vocational education will serve as an opportunity to enhance human capital. Lastly, drawing inspiration from the existing Mexican "Oportunidades" and Brazil's “Bolsa Família” policy, this paper presents a Conditional Cash Transfer policy recommendation to Cambodia to address its poverty issues.

2. Argument

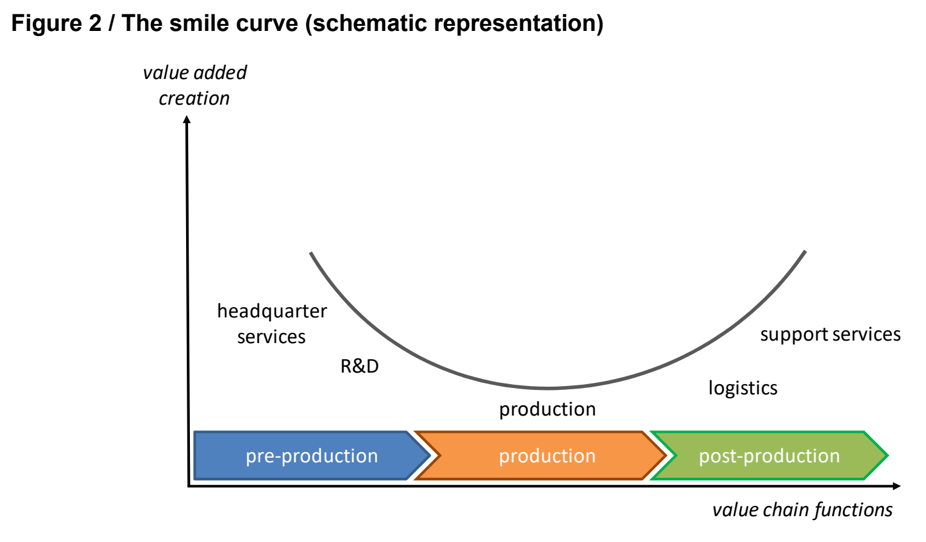

In 2019, the industrial sector in Cambodia accounted for 27.0% of total employment, with the primary revenue source being garment production [8]. The dominant model in Cambodia's garment industry still adheres to the "Cut, Make and Trim" stage. This model heavily relies on importing raw materials from countries such as China and Vietnam. In 2004, one of the founders of Acer Inc., Shih Stan, introduced the concept of the 'Smiling Curve' to represent the value-added progression in goods production [9]. As Figure 1 shows, this curve suggests that the most substantial value is added during the pre- and post-production stages, with the production task considered the minimum point on the value chain.

Figure 1: The smiling curve proposed by Shin Stan [10].

Leveraging its abundant, low-cost labor, Cambodia has played a pivotal role in the production and manufacturing of raw materials, which are subsequently handed over to foreign companies for further processing [11]. This approach places Cambodia in a challenging position, as it remains at the lowest end of the smiling curve. This limitation hinders the country from gaining a foothold in higher value-added aspects of the industry [12]. Considering Cambodia's current industrial situation, a heightened engagement of its workforce in the upper stage of the "Smiling Curve" could significantly bolster its economic growth. This shift in value-added would subsequently create an explosion in demand for skilled white-collar jobs: The emergence of educated talents who were familiar with numeracy and literacy skills could play a pivotal role in engineering, managing, and so on. Johnson characterizes the augmentation of white-collar high school education as a significant "rescue" factor of the industrialized transition [13]. Yet, in Cambodia, currently undergoing a similar automation shift, it seems to deviate from this transformative path. Despite Cambodia’s compulsory nine-year education system, merely 21.9% of individuals over 25 years of age have completed elementary schooling. Although recent years have witnessed a rise in school attendance rates, the statistic suggested in 2017, 11.7% of Cambodians aged 6 and above had never experienced formal education [14]. This reality severely obstructs the nation's potential to pivot towards higher value-added industries, altering its path to economic transformation.

According to the National Labor Force survey, there are diverse reasons why children are not able to attend school. Less than one percent mention that no suitable schools or schools are too far away. The largest proportion, around 36.6%, mention that they have to help their families with household income, which often means engaging in informal child labor [8]. This highlights that while research models have proven that child labor isn't economically efficient for everyone [15], a one-size-fits-all government approach isn't realistic due to the harsh reality of poverty: Many children have no other option but to work even though there's the option for free schooling. Andersen highlights significant inequality in access to education and basic healthcare facilities and services within Cambodian society. These disparities are primarily attributed to government corruption, weak law enforcement, vested interests, and limited monitoring and evaluation capabilities [16].

Apart from the regular education system, the low enrollment in vocational schools in Cambodia is a worrying concern for the skill level and expertise of manual jobs. Cambodia has set up vocational education programs that start from high school. However, as of 2019, just 0.4% of working Cambodians possess a vocational certificate. What's more, the average education expense for vocational training is significantly higher, by about 20%, compared to attending a regular high school [8]. The high expenses associated with vocational training not only discourage blue-collar workers from participating but also create challenges in enhancing efficiency and expertise in production to meet the demands of international corporations.

Given the challenges confronting Cambodia in terms of poverty and education, the approaches taken by Brazil and Mexico in dealing with comparable issues are enlightening. Table 1 summarizes the basic policy framework for Brazil's Bolsa Família and Mexico's Oportunidades (now referred to as Prospera). Both nations have chosen a Conditional Cash Transfer scheme as the focal point of their strategies. This scheme grants funding to the intended public once they fulfill specific criteria set forth by the administration, which will reap lasting advantages for the public.

Table 1: Summary of CCT policy setup for Brazil and Mexico.

Program name | Country | Conditions | Transfer method | Amount of cash transfer | Target families |

Bolsa Família Program 2003- | Brazil | -Attend school regularly (more than 85% of appearance rate) -Basic vaccinations and medical examinations | Social assistance card, transfer monthly | Vary from $ 7 to $ 45, determined by the eligibility criteria based on the monthly per capita income. | -Expectant or nursing mothers, as well as children under the age of 7. -Limits set at US$ 57 per capita per month for moderately poor population, and US$ 29 for extremely poor. |

Oportunidades (Now named Prospera) 1997-2019 | Mexico | - Accepts health services (Medical check for infant, pregnant women) -Receive health education on nutrition and hygiene. | Cheques, transfer bimonthly to mothers | $35 in average, could up to $153 for multi children family | -Family below poverty line -Marginal family -Community valuation |

The advantage of Conditional Cash Transfers (CCT) over unrestricted cash transfers is evident, as emphasized by the World Bank in 2020. Unconditional cash transfers offer temporary relief, resulting in short-term improvements, but they lack sustainable impacts that address the underlying causes of poverty. In contrast, CCT programs employ a dual strategy: they provide income support while setting conditions to encourage favorable life choices. This combination facilitates the enhancement of human capital and holds the potential for lasting poverty alleviation [17].

Based on reports from Mexico and Brazil, which have been implementing CCT for over 20 years, the comes shows the program could significantly enhance school attendance rate among poor families: Prior to implementing CCT programs, both Mexico and Brazil faced challenges with high school dropout rates, which affects their human capital growth. For instance, in 2001, around nine million Brazilian youths aged 18 to 25 hadn't completed 8 years of education [18]. Similarly, Mexico struggled with early school dropout rates, with nearly 50% of 15-year-old boys participating in labor before CCT [19]. These problems mirror Cambodia's current struggles: early school dropout rates, early work initiation, and low human capital. However, after the implementation of CCT programs, both Brazil's Bolsa Familia and Mexico's Oportunidades have exhibited clear positive effects on school attendance [20]. In rural Mexico, introducing Oportunidades led to an 85% increase in children enrolling in high school [21]. Similarly, in Brazil, the school enrollment rate rose 4% in 2006, just the second year after the CCT program's launch [22]. These examples showcase how such programs have successfully improved school participation rates in both countries.

Table 2 displays the conditional cash transfer (CCT) policies proposed in this paper for implementation in Cambodia. The policies consider the fundamental structure of Oportunidades and Bolsa Familia, with added guidelines for beneficiaries in accordance with Cambodia's objective of adding higher value to the garment production chain.

Table 2: Possible policy setup for Cambodia.

Form | Conditional cash transfer (CCT) Financial support to eligible families under specific conditions. |

Target population | - Population in extreme poverty line - About 17.8% of the total population [23] - Carrying or having kids below 15 years old |

Conditions | - Children’s School official report with more than 85% attendance rate for at least one semester - Agree to receive randomized home visits (approximately once a month) - Agree to attend weekly public vocational training at village/town/neighborhoods (If available) |

Payment method | -Monthly Transfer -Once the family meets all conditions, a social assistance card will be given by the territory manager. The social assistance card only allows the withdrawal of money from the card. |

As per the proposal on vocational education, this paper argues for including free public vocational training as one of the conditions for receiving the CCT benefit. This measure aims to expedite the automation of the garment industry by enhancing the professionalization of blue-collar workers. The need for this strategy arises from the high cost of vocational education stemming from its exclusion from the compulsory system [8]. Therefore, providing cost-free vocational training as a condition for CCT could enhance vocational proficiency and overall production standards. Worth mentioning, countries are very likely to misjudge target populations when implementing CCT programs: There were inclusion and exclusion errors of beneficiaries in both Bolsa Família and Oportunidades. Indeed, it is inevitable that these programs must strike a balance between expanding coverage and enhancing efficiency in their targeting approach [20]. This paper recommends the Cambodian government prioritize minimizing exclusion errors when errors are unavoidable. On top of that, establishing a department for reporting and addressing such errors gradually can help rectify mistakes.

3. Conclusion

In the face of Cambodia’s economic challenges, the government urgently needs a transition to more advanced stages within its industrial sector. Realizing more value added in the manufacturing process is enabled by the heightened efficiency and comprehension of advanced machinery, achieved through a rise in human capita. This crucial evolution hinges on an educational investment: addressing Cambodia's prevalent dropout rates and child labor is essential for cultivating a larger population with higher education bases. In response, adopting a CCT program inspired by Mexico's "Oportunidades," emerges as a potential option. The demonstrated success in Mexico and Brazil underscores the positive impact on school attendance and the child labor issues. Additionally, this paper believes the additional CCT condition for free public vocational education will further promote the professionalization of manual workers. Meanwhile, lessons from previous instances of misidentifying target populations are proposed, followed by a potential trade-off recommendation.