1. Introduction

Photocatalytic CO₂ conversion into useful hydrocarbons (e.g., CO, CH₄, olefins, and alcohols) presents a sustainable approach to address both energy needs and climate challenges [1-3]. This artificial photosynthesis-like process was first demonstrated by Halmann et al. in 1978, who achieved CO₂ photoreduction to formic acid and methanol using a p-GaAs photocatalyst. Since then, considerable advancements have been made in developing efficient CO₂ reduction systems [4-6]. However, two major bottlenecks hinder its practical application: (1) poor solar-to-fuel conversion efficiency (<1%, far below the 10% threshold for economic feasibility) and (2) limited control over product distribution [7]. Therefore, enhancing the efficiency of photocatalytic technologies and designing effective photocatalysts to reduce CO2 emissions is of paramount importance.

The inherent thermodynamic stability of CO2 (ΔfG298° = −394.36 kJ/mol) presents a significant challenge for its reduction [8]. Most photocatalysts investigated to date involved transition metal oxides such as TiO2, SrTiO3, ZnO, CdS, and g-C3N4, as well as metal-organic frameworks (MOFs) [9-11]. However, these materials often exhibit several drawbacks, such as a wide bandgap that limits their ability to absorb sunlight, "rapid electron-hole recombination, and insufficient stability of the catalyst under reaction conditions. Advancing photocatalytic CO₂ conversion requires optimizing semiconductor properties for both activity and stability. These strategies include bandgap engineering, defect control, facet optimization, co-catalyst modification, and interface design [12-15]. However, the substantial thermodynamic barriers associated with CO2 reduction and the complex reaction mechanisms involved in producing valuable fuels (e.g., CH4, CH3OH) present ongoing challenges, e.g., high-energy barriers for multi-proton coupled electron transfer, difficult chemisorption of CO2 molecules, undesirable product distributions, and the fast dynamics of excited-state processes [16]. Such obstacles highlight the need to systematically examine the critical variables controlling photochemical hydrocarbon synthesis. Thus, summarizing past research efforts aimed at selectively generating solar fuels through CO2 photoreduction is both important and timely.

This review first examines the basic mechanisms of photocatalytic CO2 reduction, including thermodynamic and kinetic considerations as well as the underlying mechanisms. It then presents typical photocatalysts responsive to ultraviolet (UV) and visible light, discusses strategies to enhance CO2 photocatalytic reduction, and explores the future prospects and challenges in this field. This review aims to deepen our understanding CO₂ photoreduction mechanisms involved in CO2 photoreduction and guide design of high-performance photocatalysts.

2. Fundamentals of CO2 photoreduction

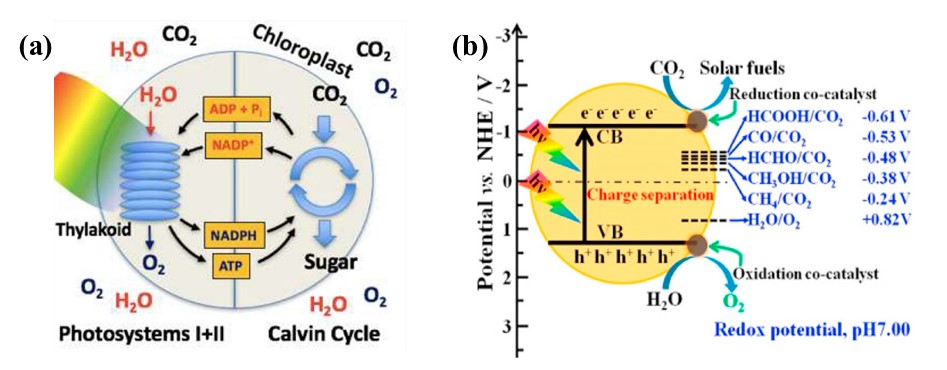

Inspired by natural photosynthesis, the photocatalytic conversion of CO2 enables efficient production of various hydrocarbon fuels including CO, methane, formic acid, and methanol (see Figure 1) [17]. The reaction pathway consists of multiple complex, sequential electron transfers taking place over a wide range of timescales (fs to s), driven by CO₂, light, and electron donors (primarily water). The performance of photocatalytic CO₂ reduction hinges on four consecutive processes: (i) CO₂ adsorption on the catalyst surface; (ii) light-induced electron excitation; (iii) charge carrier separation and diffusion to active sites; (iv) the active sites react with adsorbed CO2 molecules, converting light energy into chemical energy [18]. Therefore, key factors for efficient CO2 photocatalytic reduction include superior CO2 adsorption capability, a broad light response range, high charge separation efficiency, and favorable surface reaction kinetics.

Figure 1. Diagram showing (a) biological photosynthesis and (b) photocatalytic CO₂ conversion to fuel products

Note. (a) Reprinted with permission from ref [17]. Copyright 2017, American Chemical Society. (b) Reprinted with permission from ref [18]. Copyright 2019, Elsevier.

Photocatalyst is crucial in during photocatalytic CO2 reduction process, where its electronic structure governs both light harvesting efficiency (determined by bandgap) and redox potential (dictated by band edge positions) for driving catalytic reactions. For efficient CO₂ conversion, the photocatalyst needs (i) light-appropriate bandgap energy and (ii) conduction band levels thermodynamically favorable for driving CO₂ reduction reactions. This energetic matching enables photoelectrons to reduce adsorbed CO₂, ultimately producing renewable fuels [18]. When H₂O is present, CO₂ conversion produces various solar fuels ranging from C₁ compounds (CH₄, CH₃OH) to oxygenates (HCOOH, HCHO), with selectivity controlled by electron availability and reduction energetics [19].

The remarkable stability of CO₂ stems from its linear molecular configuration and closed-shell electronic arrangement, necessitating substantial energy (~750 kJ mol⁻¹) for C=O bond cleavage. The first electron transfer to CO₂ (forming •CO₂⁻) presents a significant energy barrier (-1.85 V vs NHE), making this step difficult to achieve with typical photogenerated electrons in semiconductor systems. In contrast, multi-electron reduction steps, aided by protons, are thermodynamically more likely to occur due to lower energy barriers. Consequently, compared to photocatalytic hydrogen production, multi-proton-coupled CO₂ reduction to CH4 and CH3OH is energetically more favorable due to lower required reduction potentials [20]. The photocatalytic reduction of CO₂ yields diverse carbon products depending on electron and photon availability, though the process is complicated by multi-electron transfer dynamics involving numerous intermediates.

The comparable thermodynamic stabilities of different CO₂ reduction products create substantial difficulties in achieving high selectivity toward specific target compounds. The surface chemistry involving reactant adsorption, intermediate transformation, and active site engagement plays a decisive role in determining catalytic performance and product distribution [21]. The adsorption and activation of CO₂ molecules on semiconductor surfaces is widely recognized as both the kinetic bottleneck and primary selectivity control point in photocatalytic reduction. Upon chemisorption to the photocatalyst surface, CO₂ undergoes a structural transformation from its linear geometry to a nonlinear structure (CO2*), substantially lowering the activation energy barrier and thermodynamically facilitating electron injection into the CO2 molecule [22,23]. CO₂ typically interacts with surface atoms through three coordination modes: single coordination with either Lewis acid sites or Lewis base sites, or mixed coordination. For instance, TiO₂ surface defects (Ti³⁺) enable CO₂ reduction to angular •CO₂⁻, with the transient Ti³⁺/Ti⁴⁺ redox couple functioning as an electron shuttle for generating key reaction intermediates [24]. This alteration in geometric structure can diminish the energetic requirements for interfacial electron transfer, accelerating CO₂ reduction processes.

Theoretical studies indicate that optimal adsorption strength of reaction intermediates is crucial for enhancing both the efficiency and selectivity of CO₂ conversion. The photocatalytic surface transforms adsorbed CO₂ into *CO intermediates that face two pathways: (i) direct CO evolution or (ii) progressive hydrogenation through *CHx (x=1-3) and *CHO intermediates [24-26]. For instance, Nørskov and colleagues demonstrated that CO was produced through *COOH intermediate, while HCOOH was generated via OCHO* intermediate, highlighting the impact of intermediate binding energies on catalytic performance [27]. By finely tuning catalytic active centers, it is possible to stabilize these intermediates effectively, facilitating surface-mediated C-C coupling and subsequent generation of multi-carbon (C₂₊) products. The dimerization of CO* on copper electrodes has been identified as a critical step in photocatalytic CO₂-to-hydrocarbon conversion. Density functional theory (DFT) studies reveal facet-dependent intermediate formation, with Cu (111) stabilizing COH* and Cu (100) preferentially generating CHO* species. On Cu (100) surfaces, C-C coupling of the dominant CHO* intermediates followed by sequential reduction enables ethylene production from C2+ species [28].

3. Photocatalysts for CO2 reduction

3.1. UV-Responsive photocatalysts

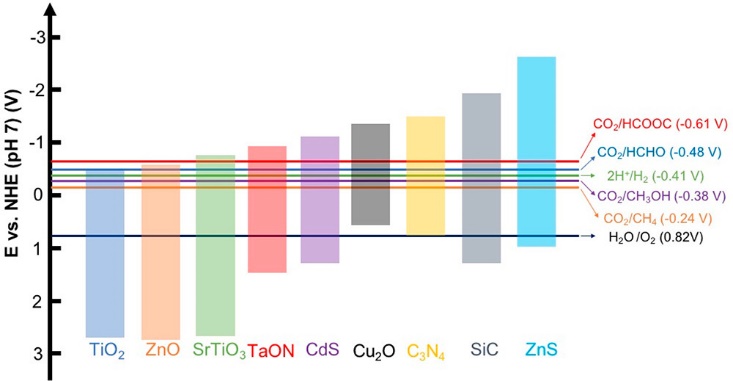

Despite accounting for merely 7% of the solar spectrum, ultraviolet radiation significantly drives photocatalytic CO₂ conversion processes. Following the pioneering demonstration of TiO₂-mediated CO₂ reduction in the 1970s, substantial efforts have been devoted to elucidating reaction mechanisms and optimizing the performance of semiconductor photocatalysts. A range of wide bandgap semiconductors has been developed, including TiO2, ZnO, and SnO2 (see Figure 2) [29,30]. Among these, TiO2 remains the most extensively researched photocatalyst for CO2 conversion owing to its robust chemical inertness, environmental compatibility, cost-effectiveness, and abundance. Nevertheless, its practical application faces limitations stemming from inefficient solar energy utilization (resulting from its large bandgap) and unfavorable charge carrier dynamics [31].

Figure 2. Typical photocatalytic materials along with their band positions, compared to the electrochemical potentials of various CO2 reduction reactions

Note. Reprinted with permission from ref (32). Copyright 2020, American Chemical Society.

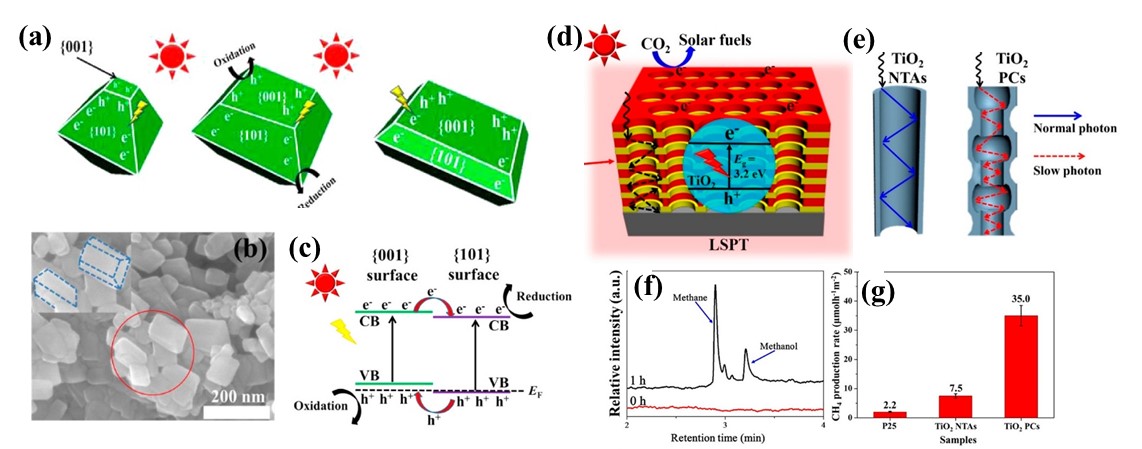

Significant efforts have been devoted to improving TiO₂'s photocatalytic efficiency through various modification approaches, such as element doping and heterostructure construction [33,34]. These modifications have significantly enhanced CO₂ conversion efficiency by facilitating charge separation, e broadening the light absorption spectrum, and stabilizing reactive intermediates. Through these strategies, researchers are working to address the inherent challenges associated with TiO2 and other wide bandgap semiconductors, enabling efficient photocatalytic CO₂ conversion. Yu et al. demonstrated that facet engineering of anatase TiO₂ could optimize CO₂ photoreduction performance (see Figure 3). DFT calculations indicated the coexposed {101} and {001} facets created an intrinsic surface heterojunction, enabling spatial separation of photogenerated charge carriers-electrons preferentially migrating to {101} facets while holes accumulated on {001} facets. Remarkably, at an optimal facet ratio of 45:55 ({101}:{001}), the CH₄ production rate increased by 21-fold, from 1.4×10⁻3 to 30×10⁻3 μmol h⁻1 m⁻2 [35]. Yu et al. further fabricated TiO₂ photonic crystals (PCs) through an innovative template-free anodization-calcination approach (see Figure 3). This unique photonic crystal structure provided TiO2 with enhanced capabilities for capturing photon energy and heat radiation. During CO₂ photoreduction, CH4 and CH3OH were identified as the primary products. Notably, the TiO2 PCs exhibited exceptional performance in CH4 production, with methane production rates reaching 15-fold and 4-fold enhancements compared to conventional P25 and TiO₂ nanotubes (NTAs), respectively [36].

Figure 3. (a) Schematic representation of the redox site distribution on anatase TiO₂ with coexposed {001}/{101} facets; (b) Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) image of anatase TiO2; (c) Illustration of the {001}/{101} facet heterojunction; (d) Schematic depiction of CO₂ photoreduction enhancement mechanism on TiO2 photonic crystals (PCs); (e) The optical pathways in TiO2 nanotube arrays (NTAs) and TiO2 PCs; (f) Gas chromatogram indicating the products from CO2 photoreduction; (g) Methane generation activity of different TiO₂ morphologies

Note. (a–c) Reprinted with permission from ref (35). Copyright 2014, American Chemical Society. (d-g) Reprinted with permission from ref (36). Copyright 2018, American Chemical Society.

3.2. Visible light responsive photocatalysts

Despite significant research into photocatalytic CO2 reduction, practical applications remain limited due to the inefficiency of these reactions in meeting industrial standards. A key challenge is the low utilization of solar energy. The fact that 46% of solar radiation falls within the visible spectrum makes improving photocatalysts' absorption in this range an attractive approach. Multiple narrow bandgap semiconductors, such as Cu2O, perovskites, and plasmonic resonance absorption-based catalysts, have shown significant promise in improving photocatalytic CO₂ reduction efficiency [37,38].

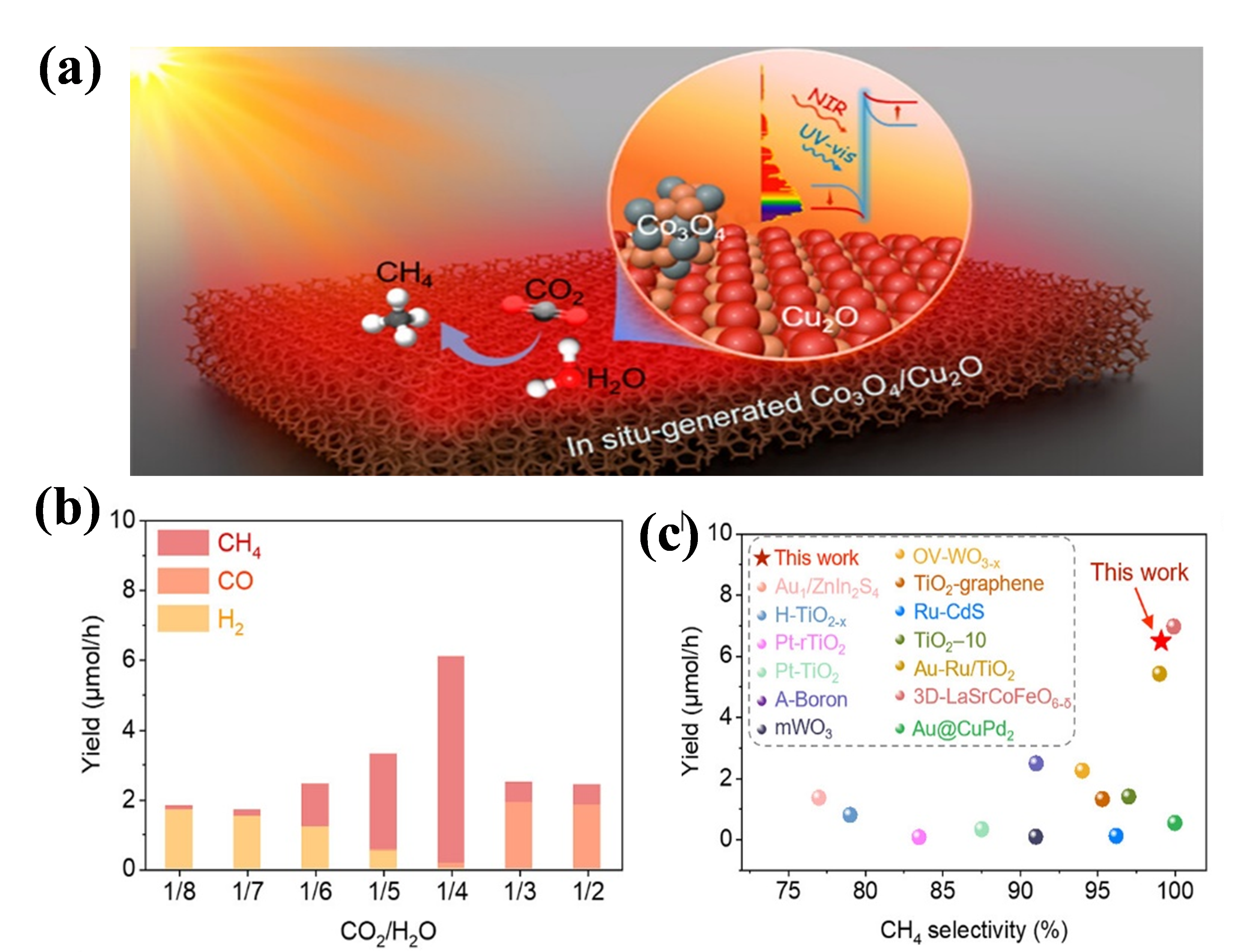

With its narrow bandgap and well-aligned band structure, Cu2O exhibits strong visible-light absorption, rendering it highly suitable for CO₂ photoreduction under visible light [39]. Liu et al. developed a branch-structured Z-scheme Co3O4/CuOx heterojunction on 3D copper foam (see Figure 4). This photocatalyst could effectively absorb full-spectrum light under natural sunlight. Its remarkable photothermal conversion performance enhanced CO2-to-CH4 conversion. Importantly, the in situ-generated Cu(I) species in the Co3O4/Cu2O system facilitated the key *CHO intermediate formation, resulting in a significant CH4 production rate of approximately 5 mol/h and a selectivity of 98.5% during a 10-hour simulated solar light source photocatalytic CO2 reduction test. The light-to-fuel efficiency was determined to be 1.45% [40].

Figure 4. (a) Schematic representation of the charge transfer pathway in Co3O4/Cu2O during light irradiation for CO2 photoreduction; (b) CO₂ conversion efficiency under simulated light sources with varying n(CO2)/n(H2O) ratios over a duration of 2 hours; (c) Comparison of CH4 yield and selectivity against previously reported photocatalysts

Note. Reprinted with permission from ref (40). Copyright 2023 American Chemical Society.

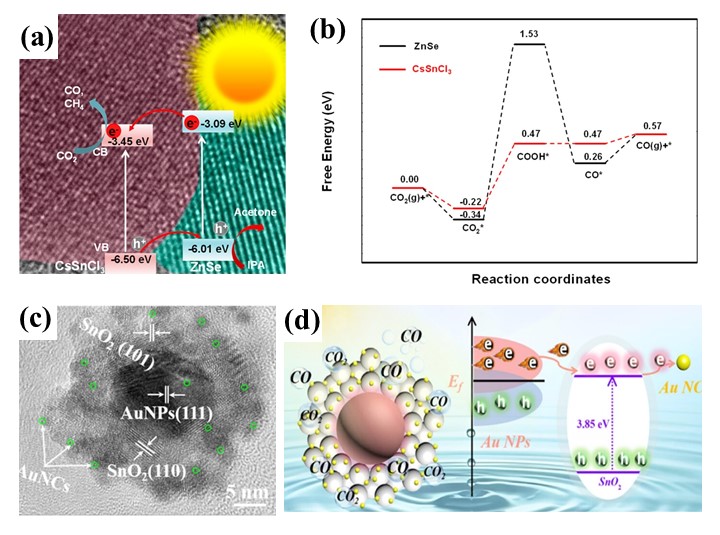

Owing to their outstanding light absorption properties, adjustable band structures, and excellent charge transport capabilities, perovskites have recently emerged as promising photocatalysts. These properties position perovskites as promising candidates for photocatalytic CO2 reduction. Their abundant surface binding sites, coupled with an adjustable composition, allow for the customization of surface electronic states and the manipulation of adsorption and desorption behaviors [41]. Such features are crucial for enhancing CO₂ conversion efficiency. Wu et al. developed Cs3Sb2I9 perovskite microcrystals using a straightforward hot-injection method, which demonstrated excellent photocatalytic performance under visible light (7.1 μmol g⁻¹ CO production, 100% selectivity) (see Figure 5a, b). This superior performance results from low carrier recombination, efficient separation of charges, and suitable energy band alignment [42]. Wang et al. successfully synthesized a ZnSe–CsSnCl3 heterojunction using an electrostatic self-assembly method, achieved a visible-light-driven CO₂ reduction rate of 57 μmol g⁻¹ h⁻¹, fivefold higher than pure ZnSe nanorods. This enhancement stems from improved charge separation, reduced energy barriers for CO₂*→COOH* conversion, and abundant active catalytic sites on CsSnCl3 perovskite [43].

Figure 5. (a) Proposed CO2 photoreduction mechanism over ZnSe–CsSnCl3 composite; (b) Comparative DFT analysis of CO2 reduction energetics on CsSnCl3 versus ZnSe; (c) HRTEM image of AuNPs@SnO2–AuNCs; (d) Reaction pathway for CO2 conversion over AuNPs@SnO2–AuNCs

Note. (a, b) Reprinted with permission from ref (42). Copyright 2021, American Chemical Society. (c, d) Reprinted with permission from ref (45). Copyright 2024, American Chemical Society.

Metallic nanoparticles (Ag, Au, Cu) exhibit distinctive optical characteristics through localized surface plasmon resonance (LSPR), garnering significant research interest. Under visible/NIR illumination, collective electron oscillations in metal nanostructures create confined thermal fields through lattice vibration-mediated energy dissipation. The hot electrons produced in metallic nanoparticles can be injected into semiconductor materials, facilitating broader spectrum absorption and enhancing electron participation in CO2 reduction reactions [44]. Fang et al. developed a hybrid structure comprising Au nanoparticle (AuNPs)@SnO2 decorated with Au nanoclusters (AuNCs) (see Figure 5c, d). The LSPR effect of the AuNPs facilitated the transfer of plasmon-induced hot electrons to the active sites of the AuNCs, enhancing photocatalytic CO2 reduction. This dual coupling between AuNPs and AuNCs resulted in an impressive CO production rate of 64.8 μmol g⁻1 h⁻1, representing 2.6-fold and 4-fold enhancements over the SnO₂-AuNCs (25.3 μmol g⁻1 h⁻1) and AuNPs@SnO₂ (16.0 μmol g⁻1 h⁻1), respectively [45].

4. Engineering strategies for enhancing photocatalytic activity

4.1. Co-catalysts engineering

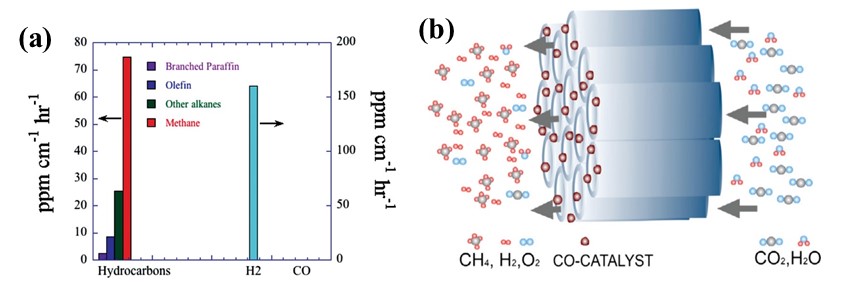

Cocatalysts are substances that synergistically enhance the performance of photocatalysts. They function not only as electron traps to capture photogenerated charges, thereby suppressing recombination, but also as active sites that reduce the activation barrier for redox reactions. These effects collectively enhance CO₂ adsorption and conversion efficiency, ultimately boosting both the activity and selectivity of the photocatalytic process. Typical types of cocatalysts include biocatalysts, molecular complexes, metals/alloys, metal oxides, and carbon-based materials [46,47]. Notably, copper (Cu) exhibits exceptional potential due to its favorable adsorption properties—strong binding with *CO while weakly adsorbing *H—making it highly selective for CO₂ reduction. Using Pt- and Cu-decorated nitrogen-doped TiO₂ nanotube arrays, Grimes et al. attained a CHx generation rate of 111 ppm cm⁻2 h⁻1 under standard AM 1.5 solar illumination (see Figure 6) [48].

Figure 6. (a) Product formation rates using Pt/Cu-modified N-doped nanotube arrays;

(b) Schematic of flow-through membrane design for enhanced CO₂-to-fuels conversion

Note. Reprinted with permission from ref (48). Copyright 2009 American Chemical Society.

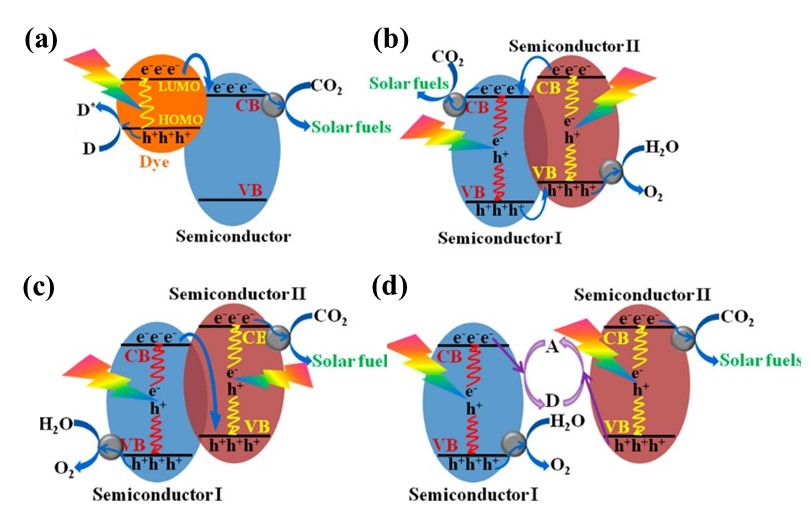

4.2. Heterojunction engineering

Despite numerous strategies to improve semiconductor performance, inherent limitations such as short carrier lifetimes and poor quantum efficiency remain key bottlenecks in advancing CO₂ photoreduction efficiency. This is primarily due to the fact that the charge recombination process (approximately 10⁻⁹ seconds) occurs significantly faster than surface redox reactions (ranging from 10⁻⁸ to 10⁻¹ seconds) [49]. To address this challenge, heterojunctions have emerged as a promising approach to overcome this limitation by spatially segregating photogenerated carriers, significantly improving photocatalyst efficiency. When the energy band positions of two different compounds are suitably aligned, photogenerated charges can efficiently traverse the interface and transfer to the two components of the heterojunction, where they undergo distinct oxidation and reduction reactions. In recent years, researchers have developed various photocatalytic heterostructures systems. Based on light collection and charge transfer characteristics, current approaches to photocatalytic CO₂ reduction fall into three main categories (see Figure 7): photosensitized semiconductors, dual-excitation heterojunctions, and Z-scheme configurations [50].

Figure 7. Illustrations of the primary mechanisms for charge separation during photocatalytic CO2 conversion,

including (a) semiconductor photosensitization, (b) dual-excitation heterostructure, (c,d) Z-scheme configurations

Note. Reprinted with permission from ref (50). Copyright 2016 American Chemical Society.

4.3. Defect engineering

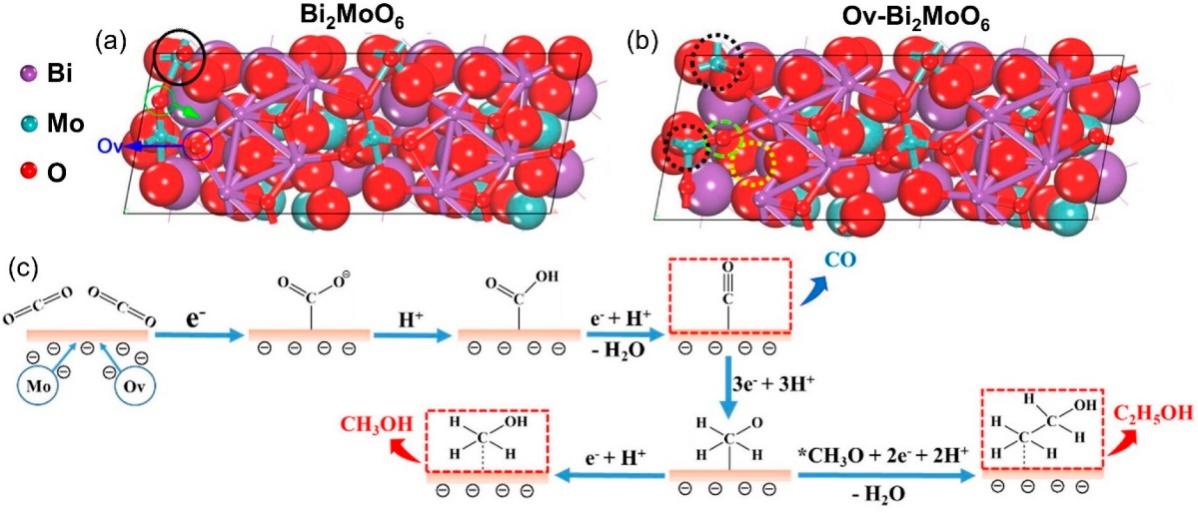

Defects are inherent missing or irregular structures within a material's lattice. These defects can significantly boost photocatalytic performance through enhanced carrier separation, broadened spectral response, and provide additional catalytic sites, making them advantageous for CO₂ conversion. Two fundamental defect types are recognized: (i) Oxygen vacancies: These are formed when oxygen atoms are missing from the lattice and can promote electron localization and increase reactivity. For example, removing oxygen from metal oxides can generate lower-valence metal atoms, which not only stabilize intermediates but also facilitate C-C coupling reactions [51,52]. (ii) Element doping: Introducing metal or non-metal ions of different valences into semiconductors may alter their crystal structure and introduce new defects. Such structural changes concurrently minimize charge carrier recombination and expands the spectral response range of the photocatalyst, effectively enhancing its catalytic performance [53]. Recent advances in defect engineering have enabled precise tuning of defect characteristics in catalysts, further improving the selectivity of products in photocatalytic reactions. Dai et al. developed a 3D Bi2MoO6 material with oxygen vacancies, resulting in significantly boosted CO₂ photoreduction efficiency (see Figure 8). Such oxygen vacancies enhance photogenerated charge separation in the Bi2MoO6 structure. Additionally, the coordinatively unsaturated Mo sites created by these vacancies stabilize *CH3O intermediates and promote visible-light-activated C-C coupling [54].

Figure 8. Schematic representation of the optimized configurations for (a) Bulk-Bi2MoO6 and (b) Ov-Bi2MoO6,

(c) Proposed CO2 reduction pathways for generating CH3OH and C2H5OH on Ov-Bi2MoO6 interface

Note. Reprinted with permission from reference (53). Reprinted with permission from ref (54). Copyright 2021, Elsevier.

5. Summary and perspectives

This paper reviews the latest advancements in photocatalytic CO2 reduction systems, focusing on the fundamental theories of the reduction process, representative photocatalytic materials that perform well under UV and visible light, and key strategies for enhancing their activity and selectivity. Although some progress has been made in laboratory settings, low reaction activity and product selectivity remain significant barriers to commercialization. Therefore, numerous challenges must be addressed to realize the practical application of this artificial photosynthesis technology.

(i) Developing efficient photocatalysts that can respond to a full spectrum of light is crucial for improving CO2 conversion efficiency. This goal drives the search for photocatalysts with enhanced activity and selectivity, effectively reducing charge recombination and boosting light responsiveness. Future research should concentrate on synthesizing photocatalysts with well-defined physical and chemical characteristics while elucidating the relationship between their structure and function.

(ii) The broad product distribution in CO2 photoreduction often results in target product activity and selectivity falling short of expected standards. Integrating theoretical research with experimental techniques to explore the atomic structure of photocatalyst interfaces, and modulate intermediate adsorption/activation behaviors, will aid in optimizing the selectivity of CO2 photoreduction, facilitating higher-value hydrocarbon production.

(iii) There is currently a lack of standardized protocols for assessing the performance of photocatalytic CO2-to-fuel conversion and suitable metrics for quantifying the efficiency of CO2 conversion into specific fuels. Thus, establishing a coherent evaluation framework is vital for establishing reproducible research foundations.

In summary, engineered photocatalytic CO₂ conversion systems must simultaneously achieve robustness, reusability, non-toxicity, impressive efficiency, and broad spectrum responsiveness under sunlight will critically advance circular economy transitions while strengthening energy security and environmental resilience.